Tunnels, initially aimed at crossing an obstacle (in general a mountain), have become increasingly complex during recent years, incorporating increasingly complex equipment (including ventilation systems) and methods of operation. Such operation includes the deployment of control and supervision systems that enable the handling of vast amounts of data, and which can accommodate increasingly sophisticated management scenarios.

Figure 1: St Gotthard tunnel fire

Following the catastrophes in the Mont Blanc, Tauern and Gotthard (Figure 1) tunnels in the years 1999 and 2001, the need to adopt a holistic approach to tunnel safety was recognized. This resulted in stricter provisions from the tunnel design stage onwards, which have an important impact on specific civil engineering and tunnel equipment requirements.

In general, tunnels are considered as "expensive and risky" works, both with regard to their construction as well as their operation. This "image" makes some countries very reluctant to embark upon the construction of their first or railway tunnels. In order to address such concerns, increasing importance is being given to risk management (including construction and operation costs), accident or fire mitigation during operation and the optimisation of the tunnel facilities at the design, construction and operation stages. This risk and cost management is reinforced through current procurement and financing models for the construction of tunnels, which are increasingly being implemented as "Concession", "Design and Build" or "Private Public Partnership" models.

The chapter entitled Strategic Issues aims to:

This chapter is not designed to be a detailed handbook of the actions required by tunnel owners, or to specify the technical provisions to be implemented by designers, or to determine the tasks to be undertaken by operators to ensure a safe and comfortable tunnel environment. In particular, this chapter does not aim to be a design handbook. Its main objective is to make the reader aware of certain issues, in order to facilitate comprehension of this complex field, to raise awareness of the many possible errors in tunnel operations, and to have a better understanding of optimisation possibilities.

The page entitled Tunnel: a complex system, explains why a tunnel constitutes a "complex system" and lists the main interfaces between Civil Engineering, Ventilation and Safety aspects;

The page Steps of tunnel life analyses the various stages of a tunnel’s life cycle and underlines the key actions of each of these phases;

The page General design of the tunnel (new tunnel) presents the major elements which have to be considered when designing a new tunnel;

The page Renovation - Upgrading of existing tunnels concerns the upgrading and the refurbishment of existing tunnels under operation;

The page Costs of construction - Operation - Upgrading - Financial aspects explains issues relating to construction, operation and renovation costs, as well as the main issues specific to the modes of financing;

The page Complex underground road networks highlights the special features of complex underground and interconnected structures and provides case studies of complex tunnels via numerous monographs.

The page Regulations - Recommendations gives a list of the main recommendations, directives and regulations published by various countries in Europe and elsewhere in the world.

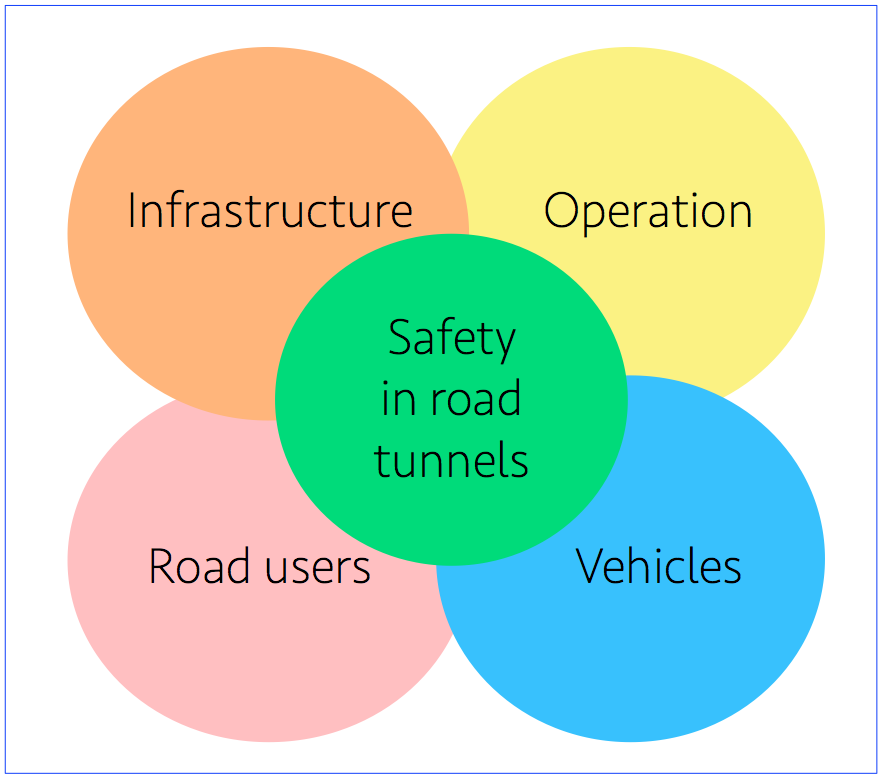

A tunnel constitutes a "complex system" which is the result of the interaction of very many parameters. These parameters can be gathered by subsets, the principal ones of which are represented in the diagram below (fig. 1).

All these parameters are variable and interactive, within each subset, and between the subsets themselves.

The relative weighting of the parameters and their character varies according to the nature of each tunnel. For example:

Fig. 1 : Diagram of main subsets of the "complex tunnel system"

Note 1: the links are multiple and often reversible - the general concept of the tunnel and the functional section are placed in the centre of the figure. Similar diagrams could be drawn up while placing other factors in the centre of the figure.

Note 2 : the first circle represents "technical fields". Some fields represent multiple aspects:

Note 3: the second circle represents the "context" in which the project is to be developed. Some elements represent multiple aspects:

The design of a new tunnel (or the refurbishment and upgrading of an old tunnel) requires these numerous parameters to be taken into account. The decision tree relating to these parameters is complex, and requires the input of experienced multidisciplinary parties. They must intervene as early as possible, for the following reasons:

Each tunnel is unique and a specific analysis has to be developed, while taking into account all the specific and particular conditions. This analysis is essential to bring suitable answers and to allow:

There is no "magic key solution", and a simple "copy and paste" process is almost always unsuitable.

The design and optimisation of a tunnel require:

Several examples are given below showing how it is possible to clarify the complexity, the interactivity, as well as the iterative and "circular" character of the analysis.

These examples are not exhaustive. Their aim is simply to make the reader aware of the issues and make it possible to focus considerations on each specific tunnel.

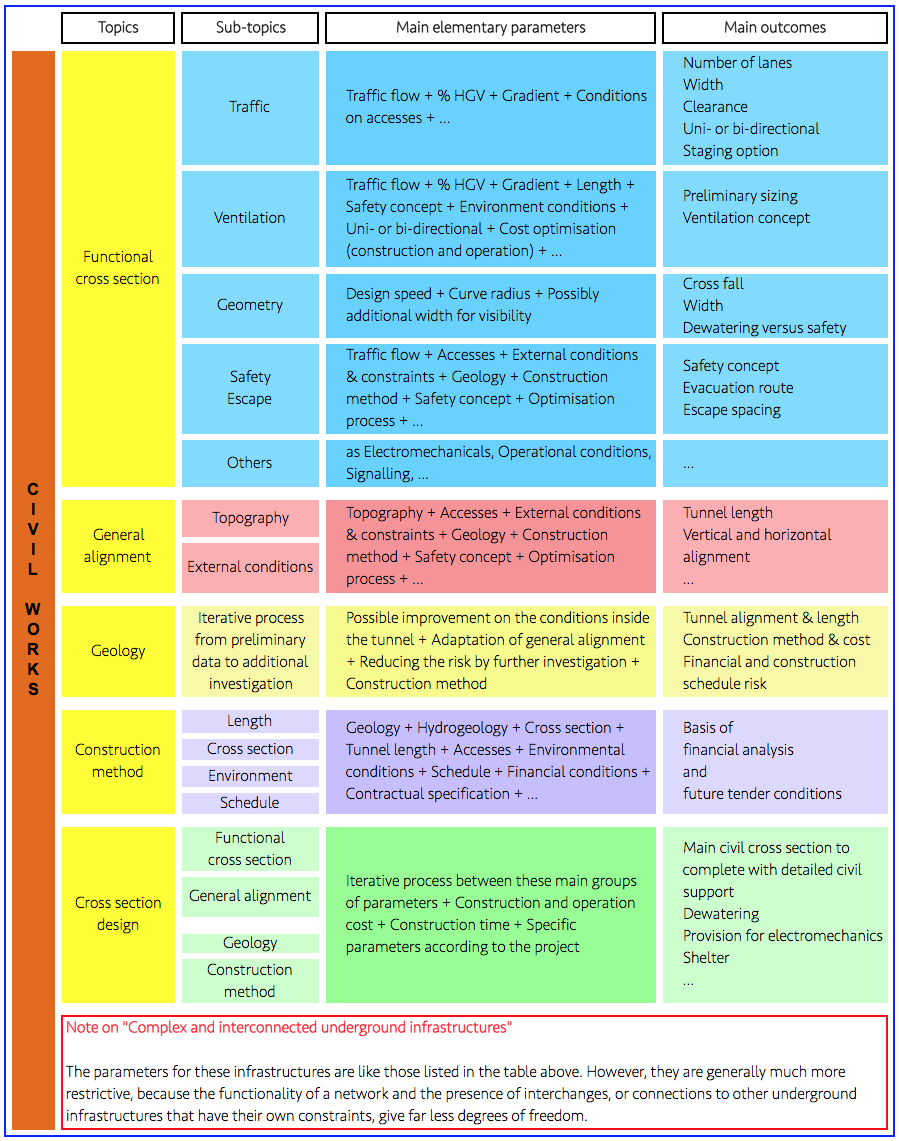

Table 1 below gives an example of the principal parameters concerning the aspects relating to civil engineering:

The first column of the table indicates the principal sets of parameters,

The interactions between parameters are numerous and often connected by circular links taking into account the overlaps between the various parameters.

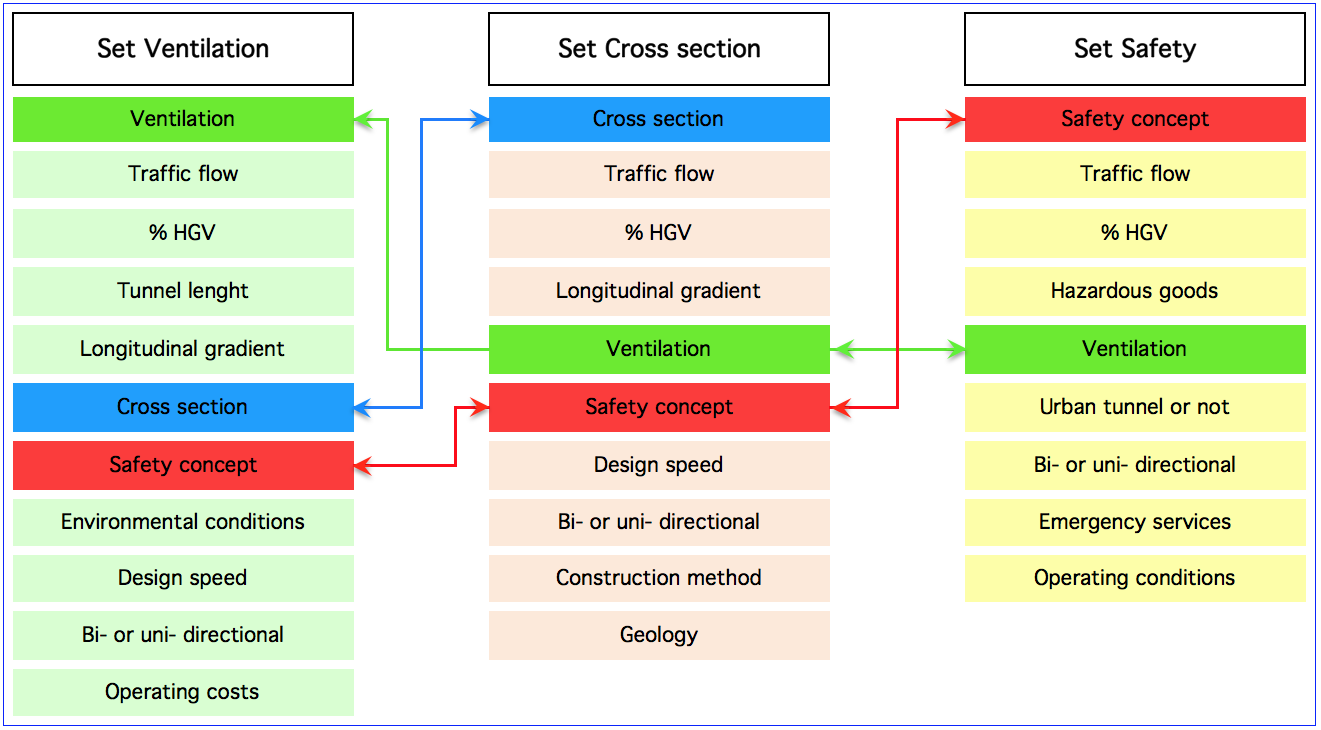

The example below (Table 2) relates to the interactions between ventilation, the cross section, and safety:

TABLE 2 : INTERACTIONS BETWEEN PARAMETERS

The table reveals a certain number of parameters common to several columns (see line connectors), which create circular interactions between the various subsets of parameters.

These interactions are linked by complex functions, which make a purely mathematical resolution of the problem nearly impossible. The resolution of the problem requires the definition of a hierarchy between the various parameters, followed by taking into account assumptions for the parameters of higher hierarchy. This hierarchy differs from one project to another, such as for example:

The process of resolution is then iterative and based on a first set of assumptions, as the previous examples show. This process requires a large transverse multi-technical experience of the engineers, making it possible to take into account the relevant parameters for the project, to better target the successive iterations, and to guarantee the best optimisation of the project, with the required level of service and safety.

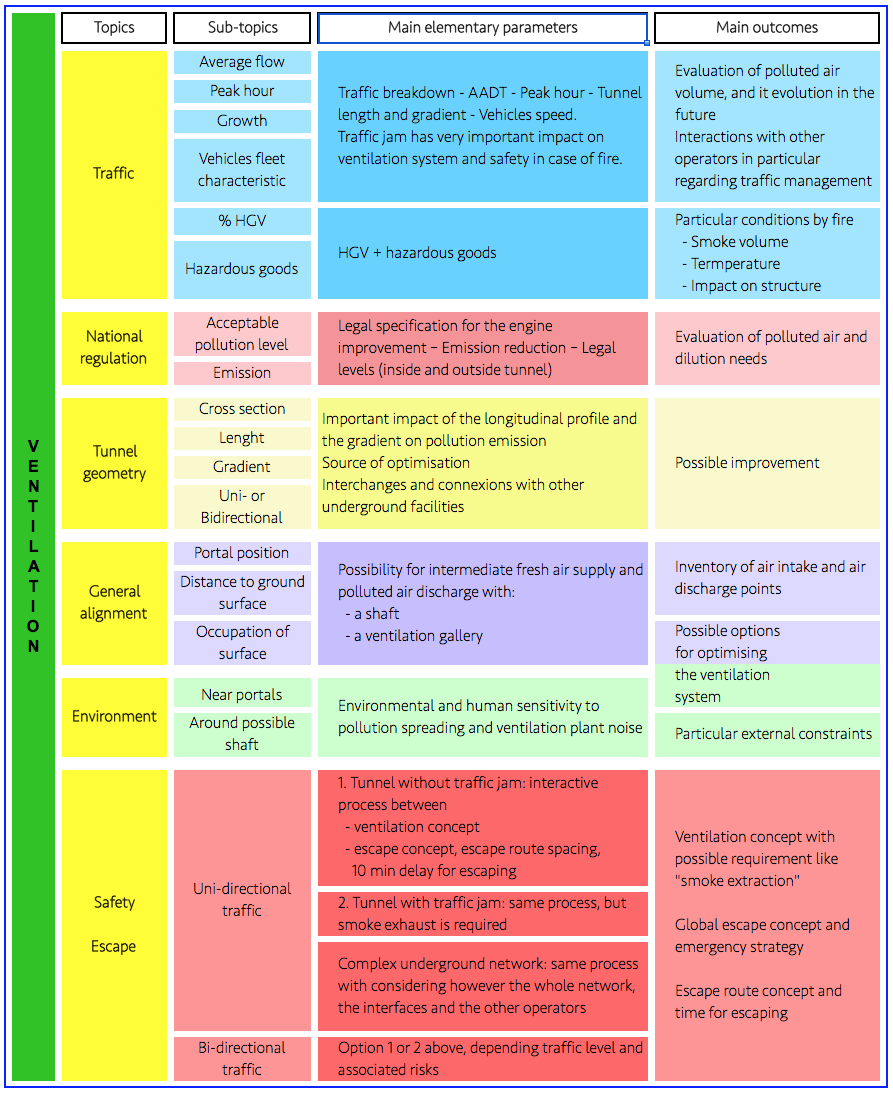

Table 3 below gives an example of the principal parameters concerning the aspects relating to ventilation. This table is not exhaustive.

As for "civil engineering", the interactions between parameters are numerous. They also are subject to circular relations.

The process to solve the problems is similar to the one outlined above for "civil engineering".

Table 3 : Main parameters influencing ventilation

4. Subset "Operation equipment"

They do not constitute fundamental parameters for the definition of the functional section, with the exception of:

"Operation equipment" constitutes on the other hand essential parameters for the dimensioning of the technical buildings at the portals, of underground mechanical and electrical sub-stations, and of all underground technical spaces, or various provisions, recesses and niches. They often require particular arrangements concerning temperature, air conditioning, and air quality.

They also are important parameters in terms of cost: construction, operation and maintenance.

"Operation equipment" constitutes essential parameters regarding tunnel safety. It must be designed, built and maintained in this objective:

The statistics available in many countries show, quite generally, that the rate of tunnel accidents is notoriously lower than that for the road network in the open air.

Apart from disasters, almost all the accidents recorded and documented in tunnels are mainly due to the following causes:

Safety aspects are to be broken down into:

Note: Additional information on tunnel accidents is available by following hyperlinks:

Fig. 2 : Factors affecting safety

The infrastructure is an essential parameter concerning the safety inside the tunnel (preventative and curative provisions), as well as the construction cost. However, one can invest highly in infrastructure without improving conditions of safety if essential provisions are not considered in parallel concerning:

These parameters relating to safety may affect in a more or less important way a tunnel project. The tables below give some examples.

Note: The four tables below refer to the four principal fields represented in Fig. 2.

| INFRASTRUCTURE | IMPACT | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|

|

Visibility – Legibility – Exit and merging conditions on the interchanges and connections with other underground infrastructures |

|

Horizontal and vertical alignment - Coordination layout/vertical profile - Design of the interchanges and connections - Design of the ramps - Exit and merging areas |

|

Escape route |

|

Inside the tunnel - Parallel gallery - Direct external access - Connection between two tubes |

|

Emergency team accesses |

|

From the other tube - Dedicated access - Common with escape route |

|

Volume of people to escape |

|

Size of escape route - Spacing of the connections to the tunnel |

|

Ventilation |

|

Ventilation concept - Inadequacy of pure longitudinal system under certain operating and traffic conditions |

| OPERATION | IMPACT | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|

|

Response plan procedure |

|

Signalling - SCADA - Communication with the users |

|

Intervention rescue team |

|

Size of the portal building - Eventual underground facilities - Specific tool - Size of water tanks |

|

Team training |

|

Particular external facilities - Special software |

| VEHICLES | IMPACT | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|

|

Traffic flow average and peak hour |

|

Number of lanes - Ventilation concept and sizing |

|

Transport of dangerous goods |

|

Ventilation impact - Particular drainage for hazardous goods spillage - Operating procedures with particular convoy with fire brigade accompanying --> parking facilities and staff |

|

State of the vehicle |

|

In particular condition, size control and overheat control before entering --> gantry heat control + parking + staff |

|

Restriction of particular vehicle categories |

|

Example: urban tunnel dedicated to light vehicles - Tunnel size, ventilation escape routes |

| ROAD USERS | IMPACT | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|

|

Information |

|

Leaflet distributed before entering - TV information campaign |

|

"Live" communication |

|

Signalling, VMS, radio broadcast, traffic lights, impact on cross section, mechanical and electrical equipment, SCADA, sometimes remote barriers |

|

Teaching |

|

Driving school (in several European countries) |

|

Guidance to escape routes |

|

Signalling - Handrail - Flash - Noise - Impact on mechanical and electrical equipment and SCADA |

|

Speed and spacing between vehicles control |

|

Radar and spacing detectors - Impact on mechanical and electrical equipment and SCADA |

A tunnel is a "complex system" which means in particular that:

Partial treatment of problems is unfortunately still rather frequent, due to lack of sufficient "tunnel culture" of the various actors involved in the design.

Control of this complex system is difficult but essential in order to:

In a parallel way the control of this complex system very often contributes to the technical and economical optimisation of the project, by a clear and early definition of the functions to be ensured and by using a value engineering process.

Taking into account, from the start of the project, the major issues relative to:

constitutes an effective approach to solving this complex equation.

The definition of the “tunnel function", as well as the "preliminary risks and dangers analysis" are often neglected or superficially treated. They are, however, an essential and indispensable "tool" for the technical, economical and safe optimization of a tunnel.

The " preliminary risks and dangers analysis " should not be confined to tunnel fires and constructive and operational provisions to minimize risks. It must also consider (which is rarely the case) the daily safety conditions to reduce the likelihood of incidents and their severity. This implies an analysis of the horizontal and vertical alignments, of the geometry of the ramps of the underground connections, of the visibility, of the likelihood of traffic congestion. This analysis must be done during the design of the alignment, while it is then still possible to improve the project in order to reduce the risk of incidents.

The key items to consider during each stage of the tunnel life are presented below.

This is the most important stage of the life of a new tunnel. It is has significant influence on construction and operation costs, safety, as well as management of the technical and financial risks.

This stage requires a transverse integration of all interfaces of the “complex system" that constitutes a tunnel. This integration has to start from the earliest stage of the design.

Experience testifies to the fact that this is unfortunately rarely the case and that often the design of a tunnel results from a succession of stages considered as independent. We note that :

With regard to civil engineering, the most important aspect is the management of technical risks (in particular geological) and of all the resulting consequences concerning construction costs and duration.

Considerations relating to risk management for construction have to be taken into account from the design stage. These considerations must be detailed and shared with the owner of the tunnel. Decisions concerning the risks must be developed and clearly documented.

The decision to take some risks does not necessarily constitute a mistake and must not necessarily be forbidden. For example working to a tight schedule does not allow the implementation of all the investigations that would be required to eliminate all uncertainties.

However, the decision to take a risk must result from a very detailed and soundly argued consideration of:

Taking a risk must not be the result of carelessness or incompetence of the various parties.

With regard to operational facilities, the reader’s attention is drawn to:

This stage of the "tunnel life" is often under-estimated and taken into account tardily. It requires taking time that is not often granted, and leads to the commissioning of the tunnel under unsatisfactory conditions, or even under conditions that highly expose safety risks.

This stage includes:

The main mission is to ensure:

It is also necessary to be able to step back and look objectively at daily routines in order to:

This page relates to the design of new tunnels. The design concerning the refurbishment and the safety upgrading of tunnels under operation is presented in page Renovation - Upgrading of existing tunnels.

The design of the horizontal and vertical alignment of a road or highway section, which includes a tunnel, constitutes a major and fundamental first stage in the creation of a new tunnel, to which the necessary attention is seldom given.

The consideration of the "complex system" which constitutes a tunnel has to start at the early stage of the design of the general alignment, which is seldom the case. It is however at this stage that technical and financial optimisations are the most important.

It is essential to mobilise from the earliest stage of the design a multidisciplinary team made up of very experienced specialists and designers, who will be able to identify all the project's potential problems, despite inevitably incomplete preliminary information. This team will be able to make good and reliable decisions for the major choices, and then consolidate these elements progressively taking into account the availability of additional information.

The objective of this section is not to define the rules regarding tunnel layout design (several countries' design handbooks are referred to in page Regulations - Recommendations) but essentially to sensitise the owners and the designers to the necessity of a global and multicultural approach, from the early stages of the design, and to the importance of essential experience that is paramount to the success of the project.

The definition of the horizontal and the vertical alignments and of the geometry of the underground interchanges or connections (in particular exit or merging areas) are an important stage in road safety. Many accidents are due to design faults as outlined in section 5.1 of page “Tunnel: a complex system” above.

The "Preliminary risk and Hazard analysis” should cover all aspects relating to geometry, legibility, visibility and the presence of any underground connections (see also section 6 of page “Tunnel: a complex system” above).

1.1. Countries without "tunnel culture"

In these countries owners and designers have a certain apprehension about tunnels. They very often prefer "acrobatic road layouts" passing along ridges, with steep gradients, huge retaining walls or very long viaducts, and sometimes tremendous consolidation works (which are very expensive and not always effective over a long period of time), in order to cross zones with active landslides.

Numerous examples of projects including tunnels and alignment variations designed with a global “system” approach demonstrate, in comparison with approaches refusing systematically the construction of tunnels:

The assistance of an external assessor makes it possible to mitigate the insufficiency or the lack of "tunnel culture", and to improve the project significantly.

The concept of a "complex system" is seldom integrated upstream, to the detriment of the global optimisation of the project. Too often the "geometry" of the new infrastructure is fixed by layout specialists without any integration of the whole set of constraints and tunnel components.

It is however essential to take into account from this stage all the parameters and interfaces described in page "Tunnel: a complex system" above, and in particular:

The functional transverse profile constitutes the second major stage of the design of a tunnel after selecting the alignment. As for the first stage, the "complex system" approach must be taken into account in a very attentive way, as upstream as possible with an experienced multidisciplinary team. All of the parameters and interfaces described in page Tunnel: a complex system must be considered.

This second stage (functional transverse profile) is not independent of the first stage (alignment), and it must obviously take into account the resulting provisions. The two stages are interdependent and very closely linked together.

Moreover, as mentioned in section 2.2 above, the process of the first two stages is iterative and interactive. There is no direct mathematical approach to bring a single response to the "complex system" analysis. There is also no uniqueness of answer but a very limited number of good answers and a great number of bad answers. The experience of the multidisciplinary team is essential for a good solution to be identified quickly.

The examples quoted in section 1 above illustrate that the provisions of the "functional transverse profile" can have a major impact on the design of the horizontal and vertical alignments.

Experience shows that the analysis of the "functional transverse profile" is very often incomplete and limited to the sole provisions of civil engineering, which leads inevitably to:

The major parameters of the "functional transverse profile" are as follows:

Safety must be a permanent concern to the contracting authority, the designers and the operators.

Safety must be considered from the early stage of the preliminary studies, using tools adapted to each of the design stages, of the tenders, of the preparation for the operation, and then during the operation period.

In a very schematic way:

The "Risk and hazard analysis" provisions, as well as the "Emergency response plan" are specified in the Book Safety.

3.2. General provisions

PIARC's recommendations are numerous in the fields of safety and operation for the finalisation of safety studies, the organisation of operation and emergencies, as well as the provisions for operation. The reader is invited to refer to theme : see book Safety.

This present chapter primarily treats safety and operation interfaces within the "complex system". The tables of section 5.2 of page "Tunnel: a complex system" indicate the degree of interdependence of each parameter compared to the various subsets of the project.

A certain number of parameters have a major impact from the upstream stages of the project onward. They must be analysed from the first phases of the design and deal in particular with:

These major parameters for the design of the tunnel are also the essential factors of the "hazard analysis", and drafts of the "intervention plan of the emergency teams". This is why we consider that it is essential that a "preliminary risk analysis", associated with a preliminary analysis of an "emergency response plan" should be carried out in the initial stages of the preliminary design. This analysis makes it possible to better describe the specific features of the tunnel and the functional and safety specifications which it must satisfy. It also contributes to a value engineering analysis, to a better design and to the technical and financial improvement and optimisation.

These parameters and their impacts are detailed in the following paragraphs

These parameters have an impact mainly on the functional cross-sectional profile (see section 2), and through it a partial impact on the layout:

Another fundamental traffic parameter is often neglected or deliberately evaded when designing a tunnel. It concerns the traffic congestion and the formation of "traffic jams" in tunnel. This parameter is particularly sensitive for tunnels which incorporate ramps and underground connections.

To postulate, as is often the case, that traffic management provisions will be taken to avoid the formation of "traffic jam" is fallacious and unrealistic as shown by the daily reality in urban areas. These provisions further lead to drastically reducing the volume of traffic entering the tunnel, reducing the capacity of the route and degrading the function and economic profitability of the infrastructure.

In most cases, this severe neglect inevitably leads to increased exposure of users to an unacceptable level of risk and danger.

The presence of "traffic jam" has significant impact on:

3.4. Evacuation of the users - access of the emergency teams

This is a fundamental parameter concerning the functional provisions and the general design. This parameter also often affects the alignment (direct exits to outside) and construction provisions: cross-passages - under gallery - parallel gallery - shelters or temporary refuges connected to a gallery.

Its analysis requires an integrated approach with the ventilation design (in particular the ventilation in case of fire), volume of traffic, risk analysis, drafting of the emergency response plan (in particular investigation of the scenarios ventilation / intervention) and construction methods.

It is necessary from a functional point of view to define the routes, their geometrical characteristics and spacing in order to ensure the flow of able-bodied and disabled people.

It is essential to insure the homogeneity, the legibility and the welcoming and calming character of these facilities. They are used by people in situations of stress (accident - fire), at the self-rescue stage (before the arrival of the emergency services). Their use has to offer a natural, simple, efficient and calming character in order to avoid the transformation of the state of stress into a state of panic.

Ventilation facilities designed as a pure "longitudinal ventilation" system have little impact on the "functional cross section" or on the "alignment".

This is not the case for "longitudinal ventilation" facilities equipped with a smoke extraction duct, or for "transverse ventilation" systems, "semi-transverse" or "semi-longitudinal" systems, "mixed" systems, or for ventilation systems including shafts or intermediate galleries permitting to draw or to discharge air outside other than at the tunnel portals. All these facilities have a very important impact on the "functional cross section", the "alignment" and all the additional underground structures.

The ventilation facilities of the traffic space are essentially designed in order to :

The ventilation facilities may also provide additional functions:

The ventilation facilities do not only concern the traffic space. They also concern:

The ventilation facilities have to be designed in order to be able to:

Communication with users has an important impact on the "functional transverse profile" through signalling.

The other major impacts do not relate to the whole of the "complex system". They relate to the subsystem concerning the operating equipment, in particular remote monitoring, detection, communications, traffic management, control and supervision, as well as the organisation of evacuation.

The operation of a tunnel and the intervention of the maintenance teams may require particular arrangements in order to enable interventions under full safety conditions, and to reduce restrictions to the traffic.

These arrangements concern for example the provision of lay-bys in front of the underground facilities requiring regular maintenance interventions, accessibility to materials for their replacement and maintenance (in particular heavy or cumbersome material).

The objective of this section is not to describe in detail operation facilities and equipment, their function or their design. These elements are defined in the recommendations of the current "Road Tunnels Manual", as well as in the handbooks or national recommendations listed in page "Regulations - Recommendations" hereafter.

The objective is to draw the attention of owners and designers to the particular issues peculiar to the equipment and the facilities of tunnel operation.

The operating equipment must allow the tunnel to fill its function, which is to ensure the passage of traffic, and to satisfy the double mission of providing for the users a good level of comfort and safety when crossing the tunnel.

The operation facilities must be suited to the function of the tunnel, its geographical location, its intrinsic features, the nature of the traffic, the infrastructures downstream and upstream of the tunnel, the major issues relating to safety and to emergency organisation, as well as the regulation and the cultural and socioeconomic environment of the country in which the tunnel is situated.

A plethora of operation facilities does not automatically contribute to the improvement of the level of service, comfort and safety of a tunnel. It requires increased maintenance and human intervention, which, if not implemented, may lead to a reduction in the reliability of the tunnel and its level of safety. The juxtaposition or the abuse of gadgets is also useless. The facilities must be suited, complementary, sometimes redundant (for the essential functions of safety), and have to form a coherent whole.

The facilities of operation are "living":

All these considerations lead to strategic choices of which the main ones are:

4.2.a. Energy - sources of power - electric distribution

For the tunnel equipment to function there must be a power sources. Large tunnels can require a power of several MW (megawatts), which may not always be available on site. Particular arrangements must be taken from the first stages of the design in order to strengthen and make more reliable the existing networks, or often to create new networks. The power supply is essential for the operation of the tunnel. It is also essential for its construction.

The supply of electric energy and its distribution inside the tunnel must provide:

Every tunnel is specific and has to be subjected to a specific analysis according to its geographical position, the context of the existing electrical networks, the energy supply conditions (priority or not priority), the possibility of increasing or not the power and the reliability of the existing public networks, the risks peculiar to the tunnel, as well as the conditions of intervention of the emergency services.

The facilities must be then designed consequently, and the operating procedures must be implemented according to the reliability of the system and the choices that have been taken during the design period.

The objectives concerning safety, in case of a power supply cut are:

The arrangements usually implemented for the electrical power supply are as follows:

4.2.b. Ventilation

PIARC recommendations are numerous in this field and constitute the essential international references for the conception and the design of ventilation facilities. In addition to the above, the reader should refer to the chapter on Ventilation concepts.

However, it must be remembered that even if the ventilation equipment constitutes one of the essential facilities in assuring the health, comfort and safety of the users in a tunnel, it is only one of the links of the system, in which the users, the operators and the emergency and rescue teams constitute the most important elements by their behaviour, their expertise and their capacity to act.

The ventilation facilities alone cannot deal with all scenarios, nor satisfy all the functions that might be assumed, especially concerning air cleaning and the protection of the environment.

The relevance of the choice of a ventilation system and its dimensioning requires lengthy experience, the understanding of the complex phenomena of fluid mechanics in an enclosed environment, associated with the successive stages of the development of a fire, the propagation, radiation and thermal exchanges, as well as the development and the propagation of toxic gases and smoke.

The ventilation facilities are in general energy-consuming and particular attention must be paid to the optimisation of their dimensioning and their operation, by using for example expert systems.

The ventilation facilities may be very complex, and their relevant management in case of fire may require the implementation of automated systems that allow to manage and master the situation more efficiently than an operator under stress.

As indicated in section 3.4 above, the ventilation facilities must above all satisfy the requirements for health and hygiene during normal conditions of operation, and to the objectives of safety in case of fire.

Hardiness, reliability, adaptability, longevity and optimisation of energy consumption constitute major quality criteria that the ventilation facilities must satisfy.

4.2.c. Additional equipment to the ventilation facilities

Two types of additional equipment for ventilation are often the subject of pressing demands from stakeholders, resident associations or lobbies:

A. Air cleaning facilities.

Page Tunnel impact on outside air quality deals with this question and the reader is invited to refer to it.

The implementation of air cleaning facilities is a recurrent demand of resident protection associations in urban areas. These facilities, usually installed underground, are very expensive to construct as well as to operate and maintain. They are also high consumers of energy.

Results to date are far from convincing, due in particular to important emission reductions from the vehicles, and to the difficulty for these systems to clean the very low concentrations of pollutants that are in the tunnel, contained in large volumes of air. Consequently, many systems installed in the last ten years are no longer operational.

The future of air cleaning facilities is very uncertain in countries where there is more coercive regulation, imposing more and more rigorous reductions of polluting emissions at the source.

B. Fixed fire suppression system (FFSS).

Page Fixed Fire Suppression Systems deals with this issue, and the reader is invited to refer to it.

The technologies are numerous and answer to varied criteria: fire fighting - containment of the fire - reduction of thermal radiation and temperature for the users situated in the vicinity of the fire - preservation of the tunnel structure against damage due to high temperature, etc.

These systems, even though presenting positive aspects, also present negative aspects related in particular to the deterioration of the conditions of visibility if they are activated from the start of the fire. The use of an FFSS requires a coherent approach to all aspects of the users' safety, as well as to ventilation and evacuation strategy.

The decision concerning the implementation or not of such systems is complex and has important consequences. It must be subject to a thorough reflection relating to the particular conditions of safety of the work concerned and to the added value obtained by the implementation of the system. It should not be taken under the influence of fashion or a lobby.

The FFSS requires the implementation of important maintenance measures, the carrying out of regular and frequent tests, without which its reliability cannot be assured.

4.2.d. Lighting

The recommendations of the CIE (International Commission for Lighting) have been criticised by PIARC because of the high levels of lighting to which they often lead. The reader is invited to refer to the technical report published by the CEN (European Committee of Standardization) that presents several methods including the CIE's.

Lighting is a fundamental tool to ensure the comfort and safety of the users in a tunnel. The objectives of the lighting level must be adapted to the geographical location of the tunnel (urban or not), its features (short or very long), to the volume and nature of the traffic.

Lighting equipment consumes a lot of power and developments are in progress to optimise their features and performance.

4.2.e. Data transmission - Supervision - SCADA

SCADA is the "nervous system" and the "brain" of the tunnel, permitting the compilation, transmission and treatment of information, and then the transmission of the equipment's operating instructions.

This system requires a meticulous analysis according to the specific conditions inside the tunnel, its facilities, the organisation and the mode of operation, the context of risks in which the tunnel is placed, as well as the arrangements and procedures implemented for interventions.

The organisation of the supervision and control centre has to be analysed very carefully, according to the specific context of the tunnel (or of the group of tunnels), the necessary human and material means, the missions to be assumed, the essential aid brought by the automatic devices or the expert systems to the operators in event of an incident, allowing the operators to reduce and simplify their tasks and to make them more efficient.

The detailed design of these systems is long, delicate and requires a very rigorous methodology of developing, of controlling by successive stages (in particular during factory tests), of testing, of globally controlling after integration of all the systems on site. Experience shows that the numerous errors noted on these systems come from the following gaps:

Page Supervisory Control And Data Acquisition systems (SCADA) of the manual sums up these different aspects.

4.2.f. Radio-communications - low voltage circuits

These facilities include:

4.2.g. Signalling

Signalling refers to page Evacuation route signs.

Even more than for the other facilities, an overabundance of signalling is detrimental to its relevance and objectives.

The legibility, the consistency, the homogeneity and the hierarchy of signalling (priority to evacuation signalling and information for users) have to be a priority of the signalling design inside the tunnel and on its approaches.

Fixed signage panels, traffic lanes signals, variable messages signals, traffic lights and stopping lights, signalling to emergency exits, the specific signalling of these exits, signalling of safety niches, physical devices for closing the lanes (removable barriers),horizontal markings and horizontal rumble strips are all part of the signalling devices. They assure a part of the communication with the users.

4.2.h. Devices for fire fighting

The devices for fire detection are either localised (detection of fire in the underground substations or the technical rooms), or linear (thermal sensing cable) inside the traffic space.

There are various devices for fire fighting:

4.2.i. Miscellaneous equipment

Other equipment may be installed according to the objectives and needs concerning safety, comfort and protection of the structure. Some examples are:

The upgrading (in particular for safety improvement) and refurbishment of existing tunnels in operation gives rise to specific problems of analysis and method. The degree of freedom is less than for new tunnels, because it is necessary to take into account the existing space and constraints. The technologies peculiar to each type of equipment and their integration are however identical.

The renovation and upgrading of a tunnel under operation quite often result in an increase of the construction schedule and costs, in much lower safety conditions during the works, and with badly controlled impacts on the traffic volume and conditions. These disadvantages are often the result of an incomplete analysis of the existing situation, the real condition of the tunnel, its facilities and its environment, as well as of a lack of strategy and procedures that would mitigate the effects on the traffic.

The page on Assessing and improving safety in existing tunnels proposes a methodology for the safety diagnosis of existing tunnels and the development of an upgrading programme. In addition, the page on Operation during maintenance and refurbishment works presents specific issues related to works carried out on tunnels in operation. Their dispositions help mitigate the problems mentioned above.

It is appropriate to draw the reader's attention to the key points of the following sections.

Detailed and rigorous diagnosis of a tunnel is an essential stage in the process of its upgrading or renovation. Unfortunately this stage is often neglected.

The physical diagnosis of a tunnel is required in order to:

This physical diagnosis must be supplemented by a diagnosis concerning the organisation, maintenance and operation procedures, as well as by a specific diagnosis concerning all documents relating to the organisation of safety and rescue interventions. This stage of diagnosis may eventually lead to the setting up of actions for the training of the various intervention parties in order to improve the global conditions of safety of the tunnel in its initial state prior to renovation.

The diagnosis must be followed by a risk analysis of the tunnel based on its actual state. This analysis has a double objective:

The diagnosis has to identify (without running the risk of late discoveries during the works period) if the existing facilities, supposedly in working condition, can be modified, be added to or integrated in the future updated facilities (technological compatibility - performance in particular for data collection and transmission, automatic functioning devices and SCADA).

The renovation or upgrading programme proceeds from two stages.

The development of the programme results from:

Depending on the physical environment of the tunnel and the spaces available, the optimum upgrading programme for the infrastructure or equipment may not be feasible under acceptable conditions, and that it is necessary to define a more restricted programme. This restricted programme may require the implementation of mitigating measures ensuring that the required level of safety is achieved in a global sense, after completion of the works.

The validation of the programme requires:

The upgrading or improvement programme does not necessarily require physical works. It may only require modification of the functions of the tunnel, or of the operating arrangements, for example:

The stage of design implementation and construction involves translating the renovation or upgrading programme into technical and contractual specifications and implementing it.

This stage requires a very detailed analysis of:

Tunnels are relatively expensive civil engineering structures with respect to their construction and operation. Particular attention must be paid from the beginning of the project in order to spot any possible technical and financial optimisations.

It is recommended from the first stages of the design to implement a process including:

This process will enable the optimisation of the project (construction and operation costs) and an improved management of the technical and financial risks, as well as the schedule.

The construction costs of tunnels are very variable and it is impossible to give representative ratios of costs per kilometre, because these ratios may vary in important proportions (average of 1 to 5) according in particular to:

At most it is possible to indicate that the average cost of a usual tunnel, built under average geotechnical conditions is about ten times the cost of the equivalent infrastructure built in open air (outside of urban areas).

The construction cost of a tunnel may be broken down into three types of cost:

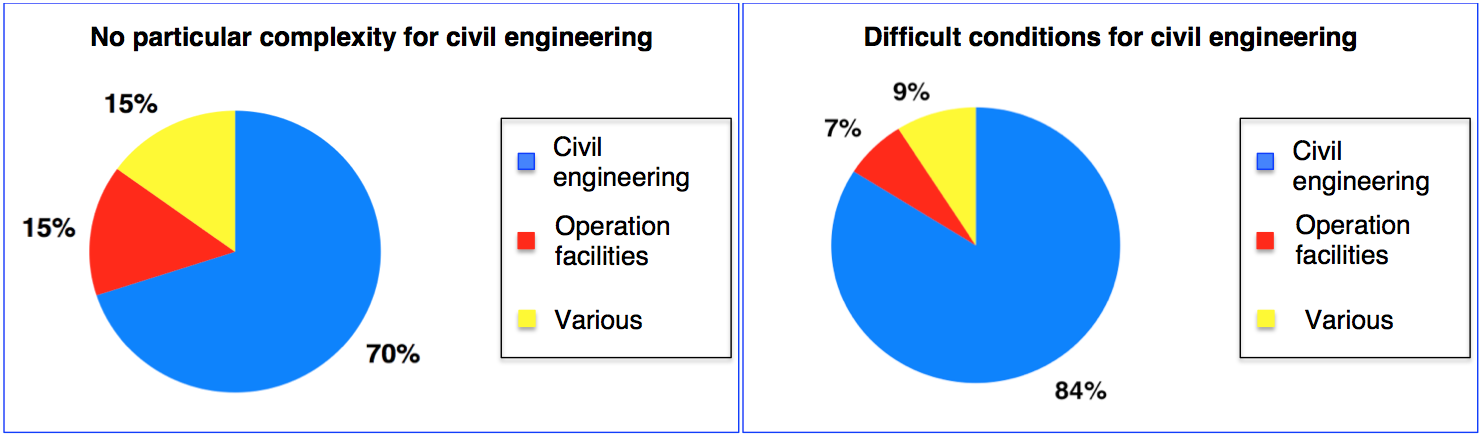

The two diagrams below show examples of the breakdown of construction costs, on the one hand for tunnels for which the conditions of the civil engineering works are not complex, and on the other hand for tunnels for which the conditions of the civil engineering works are less favourable.

Fig. 1: Breakdown of construction costs

Note: these two diagrams show how important the costs are of the civil works and illustrate the consequences of an almost doubling the costs of civil works (-hand diagram).

The operation costs of a tunnel may be broken down into three types of cost:

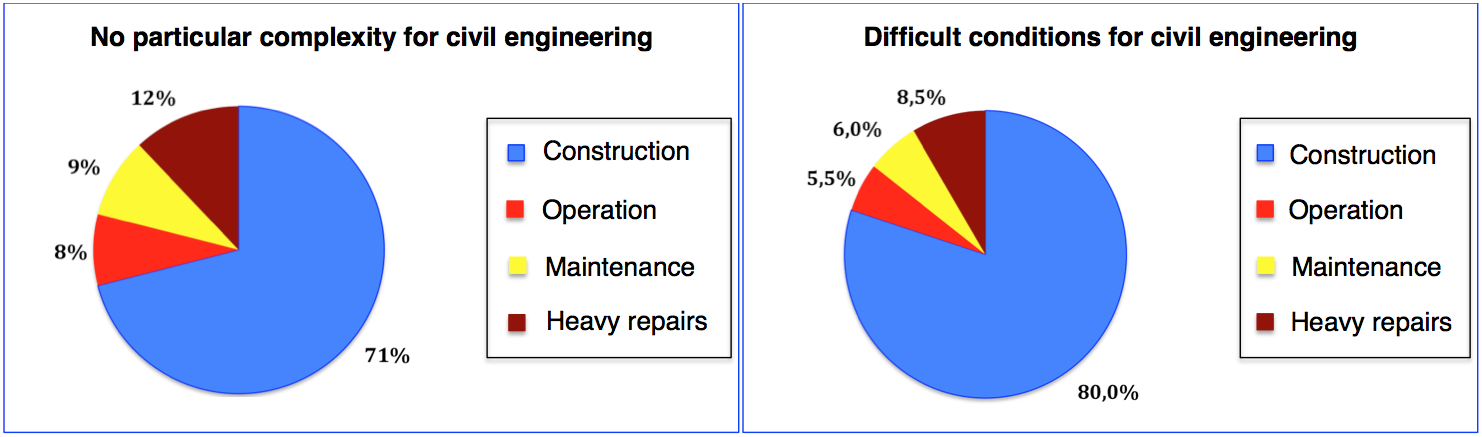

The two diagrams below represent examples of breakdown (with constant economic conditions) of the construction costs (civil works, operation facilities, various costs) and of the global operation costs (accumulated over a duration of thirty years after the start of the operation period).

Fig. 2: Breakdown of the costs during a 30-year period

Note: these diagrams show how important the operation and maintenance costs are and how it is necessary to choose from the first stages of the tunnel design the arrangements that enable the optimisation of the recurrent operation and maintenance costs.

This section concerns the renovation or upgrading works that are required for “upgrading” to new regulations. The works concern the arrangements for evacuation, the resistance of the structure to fire, the operation and safety facilities, and all the requirements to satisfy the new safety regulations.

It is not possible to give statistical prices due to the diversity of existing tunnels, their condition, their traffic and the more or less important requirements of new safety regulations that may vary from one country to another.

The observations made in France for this nature of upgrading works for complying with the new regulations, which have been carried out since the year 2000, show a large variation of the corresponding budgets with a range of costs between about ten million Euros and several hundred million Euros (there have been several upgrading programmes with a budget of more than 200 million Euros).

Tunnels constitute costly infrastructure in terms of construction and operation, but this is offset by economic benefits including regional development, traffic fluidity, comfort, safety, reliable routes (mountain crossings) as well as protection of the environment.

Financing of these works is ensured either by:

The present manual does not intend detailing these various modes of financing, or presenting their mechanisms, their advantages or disadvantages. However, it is interesting to present some main guidelines found from experience, which give a preliminary illustration.

This mode of financing is employed widely. It allows the development of an infrastructure project, whose financing could not be achieved by a “concession” (by lack of sufficient income from toll collection), or when there is political will to avoid a toll.

It requires however, that the public authority has the financial capacity to ensure this financing, or that it has the capacity to borrow money and to support a debt. The financial resources essentially come from public taxation or fuel taxes and sometimes partially from toll collection.

The financing of a “non-freestanding tunnel” by a “concession” (with or without financial involvement of the grantor) is the general case for a tunnel that is part of a new interurban highway with toll collection. The costs (construction and operation) of the tunnel are shared out among the tunnel and the linear infrastructure above ground. Experience shows that the over-cost of the average toll ratio per kilometre is accepted by the users as long as the new infrastructure brings sufficient added value concerning time savings, better or more reliable service, comfort and safety.

Two main categories of isolated tunnels exist.

The technical report 2016R19EN Road Tunnels: Complex Underground Road Networks reflects investigations carried out on case studies of complex underground road networks. A summary of this report is presented in section 2 below.

Specific recommendations will be published in a second report very soon.

The terminology “Complex Underground Road Tunnels” covers the following infrastructure:

All the structures share several similar characteristics:

The objective of the case studies was to identify structures of this type around the world, to summarise collected information, to analyse it and to establish a number of preliminary recommendations for owners, designers and operators.

While this collection of information is not exhaustive and the summaries do not constitute a scientific database, it nevertheless contains pertinent and interesting findings. The collection of information was limited to the countries of origin of the Working Group 5 members, wherein the working group had active correspondents available to them.

The general methodology has been the following:

At more than 600 pages, a significant volume of information was collected. Therefore a direct publication of all information has been deemed unsuitable. The working group decided to:

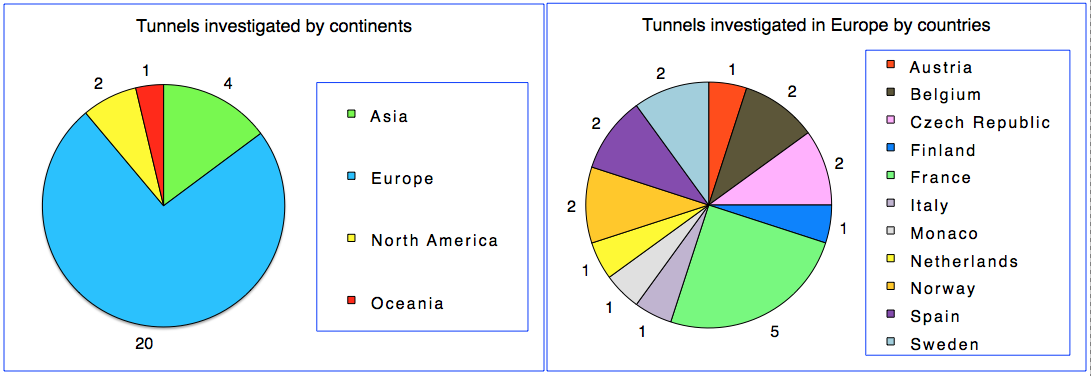

Twenty-seven (27) “tunnel complexes” were analysed. The list is provided in section 2.5 below. Several “complexes” consist of two to four tunnels and the actual analysis reflects a total of 41 individual tunnels.

The geographic distribution of structures analysed is shown in the graph below :

Fig 1 : Distribution of tunnel complexes within the case study and detailed distribution in Europe

The European tunnels seem over-represented in the sample analysis. This is due to,

The key information outlined in the analysis focuses on the following aspects:

From the analysis of information, the working group established a number of preliminary recommendations. These recommendations will be the subject of detailed additional developments which will be published in Part B of the report at the end of the 2016-2019 cycle.

These preliminary recommendations, presented in Chapter 11 - Present Situation, Comments and Preliminary Recommendations of the report, deal with the following aspects:

Underground road networks are located mainly in urban areas, and their design (in particular their alignment) has several constraints.

Geometric conditions which often contribute to traffic incidents, include: meandering curved alignment, insufficient visibility near the access and exit areas, insufficiently defined characteristics of merging or diverging lanes and, poorly designed exit ramp connections towards the surface road network leading to congestion in the main tunnel, etc.

It is recommended that in preparing the alignment, the following be considered:

b - Cross-section

The investigations mentioned above show that 80% of analysed tunnels prohibit the transit of vehicles that weigh over 3.5 tonnes (or 12 tonnes, in some instances). However, the tunnel design does not take into account this restriction, and does not reconsider optimisation of the lane width as well as vertical height clearance.

Investigations carried out on recent projects show that substantial savings (from 20% to 30% depending on the final design characteristics) can be obtained by choosing a reduced vertical height for tunnels that prohibit heavy vehicle usage.

It is recommended that at the earliest stage for developing tunnel projects detailed studies be undertaken to consider and analyse the “function” of the tunnel, traffic conditions (volume and nature of vehicles), as well as the financial feasibility and financing methods. This should be done in such a way as to analyse the advantages of a cross-section with reduced geometric characteristics. This may facilitate the financial optimisation of the project without reducing the level of service or affecting the safety conditions.

c - Ventilation

Underground road networks are usually subjected to large traffic volumes. Traffic congestion is frequent, and the probability of a bottleneck developing within the network is high and recurring. As a result, the ventilation system has to be developed with a detailed analysis of the risks and dangers, taking into account the existence of bottlenecks.

A “pure” longitudinal ventilation system is rarely the appropriate sole response to all the safety requirements, especially in the scenario of a fire located upstream of congested traffic. A longitudinal ventilation system will cause smoke de-stratification downstream of the incident location. This constitutes a danger for any tunnel user blocked or in slow moving downstream traffic.

The addition of a smoke extraction gallery or the choice of a transverse or semi-transverse ventilation system is often vital if no other realistic or feasible safety improvement measures can be put into place, and considered as efficient.

It is also necessary to implement equipment allowing the different network branches to operate inde-pendently of each other. This will facilitate the control and the management of smoke propagation during a fire incident.

The risks associated with dangerous goods vehicles travelling through a tunnel with a high urban traffic density must be carefully analysed. There are no ventilation systems capable of significantly reducing the effects of a dangerous goods large fire in such traffic conditions.

d - Firefighting

The necessary timeframe for response teams to arrive on site must be subjected to a detailed analysis under normal and peak hour traffic conditions. The objective is to determine whether or not it is necessary to install first line intervention facilities and resources in proximity of the tunnel portals.

The turnover of fire brigade staff is relatively high in urban areas and their interventions in tunnels are relatively rare. The high rate of turnover may lead to loss of specialist skills in tunnel intervention. Thus, it is essential to implement tools which allow continuous professional education and training of the teams. A virtual 3D model of the network, associated with simulation software, can provide pertinent, user-friendly and effective tools.

e - Signage

It is fundamental to ensure clear visibility of the exit ramps and a clear legibility of signage, in order to reduce the risk of accidents where exit ramps diverge from the main carriageway.

The locations of interchanges, entry and exit ramps, as well as the concept for signage should be analysed from the conceptual alignment studies.

f - Environment

In order to reduce atmospheric pollution, communities, stakeholders and residents often demand the installation of filtration devices for in-tunnel air before it is released into the atmosphere.

This results in a decision to install filtration equipment which is rarely rational or technical, but an ad-hoc response to public pressure. Before any decision-making on this issue, it is, however, essential to:

g – Traffic conditions – Traffic management

The connections between exit ramps and the surface network must be equipped in a way which allows supervision and management of traffic in real time. This arrangement allows traffic congestion to be reduced inside the tunnel, and an improvement of safety should tunnel incidents require quick evacuation of users.

h - Operation

The coordination between operators of physically connected infrastructure is in general adequate. However, it is often essential to improve this coordination by clarifying the situation and role of each operator (particularly in the event of traffic congestion and fire incident) by defining common procedures and determining priorities between the different infrastructure parts and their traffic.

Monographs have been established for each of the structures listed in the table below. They are accessible in the Multimedia Kit at the bottom of the page. The monographs of the structures highlighted in amber are in the process of being updated and will be online shortly.

| Continents | Countries | Cities | Names of the tunnels complex | Appendices |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | China (CHN) | Changsha | Yingpan Tunnel | 1-1 |

| Chongqing | Underground Ring Road of Jiefangbei CBD | 1-5 | ||

| Japan (J) | Tokyo | Chiyoda | 1-2 | |

| Yamate | 1-3 | |||

| South Korea (ROK) | Seoul | Shinlim-Bongchun and Shinlim-2 | 1-4 | |

| Europe | Austria (A) | Vienna | Kaisermühlen | 2-1 |

| Belgium (B) | Brussels | Leopold II | 2-2 | |

| Belliard | 2-3 | |||

| Czech Republic (CZ) | Prague | Blanka Tunnel complex (3 tunnels) | 2-4 | |

| Mrazovka and Strahov | 2-5 | |||

| Finland (FIN) | Helsinki | KEHU - service tunnel | 2-6 | |

| France (F) | Annecy | Courier | 2-7 | |

| Ile-de-France | Duplex A 86 | 2-8 | ||

| Lyon | Croix-Rousse (road tunnel + multimodal tunnel) | 2-9 | ||

| Paris La Défense | A14 / A86 motorway interchange | 2-10 | ||

| Voie des Bâtisseurs | 2-11 | |||

| Germany (D) | Düsseldorf | Kö-Bogen Tunnel | 2-21 | |

| Italy (I) | Valsassina | Valsassina tunnel | 2-12 | |

| Monaco (MC) | Monaco | Sous le rocher tunnel (2 interconnected tunnels with “Y” form layouts) |

2-13 | |

| Norway (N) | Oslo | Opera tunnel (chain of 4 tunnels) | 2-14 | |

| Tromsø | 3 interconnected tunnels with roundabouts and access to parking lots |

2-15 | ||

| Spain (E) | Madrid | M30 By-pass | 2-16 | |

| M30 Rio | 2-17 | |||

| AZCA Tunnel | 2-22 | |||

| Cuatro Torres Tunnel | 2-23 | |||

| Sweden (S) | Stockholm | Ring Road – Northern link | 2-18 | |

| Ring Road – Southern link | 2-19 | |||

| The Netherlands (NL) | The Hague | Sijtwendetunnel (chain of 3 tunnels) | 2-20 | |

| North America | Canada / Quebec (CDN) / (QC) | Montreal | Ville-Marie and Viger tunnels | 3-1 |

| USA |

Boston | Boston Central Artery | 3-2 | |

| Seattle | Seattle Interstate 90 Mt Baker Tunnel | 3-3 | ||

| SR 99 Alaskan Way Viaduct Tunnel through Seattle | 3-4 | |||

| Oceania | Australia (AUS) | Brisbane | M7 Clem Jones Tunnel (CLEM7) | 4-1 |

“Underground Road networks” are “complex systems”. All the recommendations presented in the 5 first pages of Chapter "Strategic issues" are applicable to them. Nevertheless, certain “subsets” and “parameters” mentioned in the page "Tunnel: a complex system" present a much more significant potential impact on underground networks. The “interactions between parameters” (see its section 2.2) are generally and much more extended and complex.

Several major strategic challenges presented in the above references, as well as their principal interactions, and the additional parameters below, must be well considered in the process of developing tunnel designs and for the construction and operation of tunnels.

This term is applicable to tunnel cross-section, vertical alignment, implementation of interchanges, access and exit ramps. In addition to the recommendations from section 1 of page "General design of the tunnel (new tunnel)" the following elements should be considered for:

a – Land occupation

Land occupation deals with the surface occupation in open air (roads, buildings and various structures, parks and protected areas, etc.) and the volumetric occupation of the underground space (underground infrastructures such as metro, car parks, various networks, building foundations, etc.)

The interfaces between the underground and surface spaces are numerous: ventilation stacks, access and exit ramps, evacuation corridors and intermediate emergency access.

The underground and surface land occupation constraints are not always compatible with a given location and it is often necessary to decouple surface structures from those underground. This relationship can be implemented through inclined shafts or underground corridors that link any vertical shafts that are located away from the tunnel alignment.

b - Geology, geotechnical, hydrogeology

The geological, geotechnical and hydrogeological conditions have a significant impact on the horizontal and vertical alignment especially with regard to the risk of settlement, the possibility of construction underneath existing structures and any required maintained distances to existing surface or underground structures, in relationship with the construction methodology considered.

These conditions can also influence the position of underground interchanges. For example, in the case of loose soil below groundwater level a localised widening of the cross section to build ramp merge and diverge areas could require construction works starting from the surface (large shafts, treatment and land consolidation works). These works require setting up temporary occupation on the surface. Under such conditions the location of underground interchanges should then also consider the type of land occupation on the surface.

c - Functionality for traffic

The functionality of the alignment mainly deals with areas where connection to the road network at the surface (or possibly with other underground structures) has to be built. The position and the design of the main tunnel portals, the access and exit ramps, as well as the location of interchanges depend on these functionalities.

The location of all these connections is also linked to the volume of traffic in the underground network, as well as its multiple entrances and exits. The connections must take into account the absorption capacity of traffic in the surface road network, adjustments to connections design in order to avoid underground traffic congestion and thus reduce accidents and significant tunnel fire incident risks.

d - Safety – Risks of accidents

The analysis of existing networks demonstrates a concentration of accidents around areas with curved geometry, overly steep slopes and insufficient visibility around the merge and diverge areas of ramps.

All these elements must be carefully taken into account from the early stage of the design of the horizontal and vertical alignments of a new network.

e - Methods of construction – Time period

The construction methodology has a direct impact on the horizontal and vertical alignments (and vice-versa). They are also strongly guided by the geological, geotechnical and hydrogeological conditions.

The methods of construction can have an important impact on the location of the tunnel portals. In particular, the use of a shield (slurry shield or earth pressure balanced) requires significant site area not only for the assembly of a tunnel-boring machine but also throughout the duration of the works (particularly for the treatment of slurry and provisional storage). A conventionally bored tunnel (when soil conditions permit it) requires fewer facilities close to the portal, and can be accommodated in a smaller site area.

The analysis for the shortening of construction timeframes can have an impact on the horizontal and vertical alignments, for example in order to make possible intermediate construction access sites.

f – Environmental conditions

During the operation period of the network, the main concerns are air quality and noise impacts. These concerns have repercussions on the positioning of tunnel portals and ventilation shafts. These issues must be analysed carefully, in particular the ventilation plants as well as the additional equipment likely to reduce the environmental impact.

The position of portals, and the associated temporary work site plants, must also be analysed from an environmental aspect in terms of construction methods and timeframes. For example, a conventional method of construction will have a more significant noise impact as opposed to a TBM construction method. If the tunnel portal is situated in a noise sensitive area, works will have to be suspended during quieter night periods, leading to a prolonged construction period and consequent inflation of costs. A modification of the portal location or changes to the alignment can reduce these impacts.

In addition to the recommendations from section 2 of the page "General design of the tunnel (new tunnel)" the following elements should be considered for:

a – Nature of traffic - Function

As mentioned in section 2.4.b above, the nature of traffic is a factor that must be carefully analysed regarding their initial conditions as well as its evolution over time. Many urban underground networks prohibit heavy vehicles (more than 3.5 t or 12 t depending on different conditions), even though they were designed with standard vertical height clearance and lane width characteristics (defined for the allowance of all types of vehicles).

Analysis of the “function” of the underground network and the evolution of that function is essential. It allows the cross-section to be optimised by choice of geometrical characteristics (vertical height clearance and lane width) to ensure adequacy for the present and future traffic that will use the network.

Savings made regarding construction costs are significant (from 20% to 30% depending on the chosen characteristics). Where applicable, these savings may allow a project to be financed, and thus feasible, where it may not have been with standard vertical clearances and lane width.

b - Volume of traffic

The volume of traffic is the determining factor in defining the number of lanes of the main tunnel, as well as interchange or access and exit ramps.

The volume of traffic should be taken into account when defining the length of merging and diverging lanes for entrances and exits. The risk of congestion, at the connection of exit ramps to the surface network, must also be considered, as well as the consequences that this has on the main tunnel (bottleneck queue) to determine whether or not it is necessary to design and lengthen a parallel lane upstream from the divergence point of the exit ramp from the main road.

c - Ventilation

The ventilation galleries to be installed inside the structure contribute considerably to the spatial requirement. Therefore, it is necessary to proceed to a preliminary “analysis of hazards and risks”, and an initial sizing of ventilation installations before definitively setting the characteristics of the functional cross-section. This approach is often iterative.

d – Geology - Geotechnics - Hydrogeology - Methods of construction

The geological, hydrogeological and geotechnical conditions, as well as methods of construction (which are often interlinked) have a vital impact on the shape and surface area of the cross-section. The following example illustrates this interaction.

In loose soil below groundwater level, the use of a shield will be required for the construction of the main tunnel. The main tunnel will be circular in shape. However, the cross-section will also depend on other functions:

Recommendations in section 3 of page "General design of the tunnel (new tunnel)" are also applicable to “underground road networks”. The analysis approach must, nevertheless, take into account the complexity of underground networks and the aggravating influence of certain factors, in particular:

a - Traffic

The volume of traffic is generally more significant and in high traffic volume conditions traffic congestion is much more frequent. It follows that the number of persons in the tunnel is much higher and in the event of an incident, the number of users to evacuate will be more significant.

Ramp merge and diverge areas are important locations in terms of risk of accidents.

The assumption, which is sometimes prevalent from the start of projects, that there will never be a traffic blockage must be analysed with much circumspection. It is indeed possible to regulate the volume of traffic entering into an underground network in order to eliminate all risk of bottlenecks. Nevertheless, this leads to a significant decrease in the capacity of the infrastructure (in terms of traffic volume) which often goes against the reasoning that justifies its construction. Over time, measures of reducing entering traffic must be relaxed, or even abandoned because of the need to increase traffic capacity. The probability and recurrence of bottlenecks increase, disregarding the initial assumption upon which the network was based (particularly in terms of safety and ventilation during incidents).

b - Emergency evacuation – emergency access

The analysis must take into account:

c - Ventilation

The concept and design of ventilation systems must take into account:

d – Communication with users

Communication with tunnel users must be reinforced and adapted throughout the multitude of branches within the network. Communication must be able to be differentiated between the different branches according to operational needs, especially in the case of fires.

Users must be able to identify their position inside the network, which would require, for example, the installation of specific signs, colour codes, etc.

Directional signs and prior information signs at interchanges or ramps must be subjected to careful consideration, particularly the visibility distances with regard to signals and the clear legibility of the signage.

e – Operational needs

Specific operational needs (see section 3.6 of page "General design of the tunnel (new tunnel)") must be adapted to the complexity of a network, to the volume of traffic and to the resulting increased difficulties of achieving interventions under traffic conditions.

Recommendations in section 4 of page "General design of the tunnel (new tunnel)" are also applicable to “underground road networks”. Nevertheless, analyses must take into account the complexities of underground road networks and the supplementary needs or conditions mentioned in section 3.

The interfaces between operators of associated or related network must be subjected to a specific analysis, particularly for all aspects concerning, on the one hand, traffic management and, on the other hand, safety (especially fire incidents), including evacuation of users and intervention of emergency response agencies in response to fire incidents.

Control centres must take account of the interfaces within the network and between diverse operators. They must allow the transmission of common information which is essential to each operator, and facilitate the possible temporary hierarchy of one control centre over another. The architectural design of the network of control centres, and of their performance and methods, must be subjected to an overall analysis of organisations, responsibilities, challenges and risks. This analysis should reflect a range of operational conditions such as during normal and emergency scenarios and should review the interaction between the different subsections of the network and the respective responsibilities of each control centre.

Countries that have many tunnels are endowed with regulations and have developed recommendations and guidelines for the design, construction, operation, maintenance, safety and the intervention of the rescue services.

Concerning safety conditions in road tunnels, countries belonging to the European Union are subjected to Directive 2004/54/CE that prescribes a minimum level of arrangements to be implemented in order to ensure the safety of users in tunnels longer than 500 m that are part of the trans-European road network. A wider group of European countries are also bound by an international convention, The European Agreement concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Road (ADR) and includes specific arrangements for tunnels. Every member country has transposed these European regulations to its own national legislation. Some member countries have implemented additional regulations that are more demanding than the one that results from the transposition of the European regulation.

A list of the regulations and recommendations concerning the operation and the safety of road tunnels has been established in cooperation between the PIARC and the ITA Committee on Operational Safety of Underground Facilities (ITA-COSUF) of the international tunnelling and underground space association (ITA - AITES). This document can be consulted on the ITA-COSUF (Publications) web page. This list is not exhaustive but presents an international panel of twenty-seven countries and three international organisations.

Many countries do not have any regulations relating to tunnels and to tunnel safety, because they do not have road tunnels within their territory. It is recommended that these countries choose a complete and coherent package of the existing regulations of a country with lengthy experience in the field of tunnels, and not to multiply the origins of the documents by dipping into different sources. The recommendations of PIARC, as summarised in the present manual, as well as those of European directive 2004/54/EC also constitute international references that are being applied increasingly often.