Without efficient operation and maintenance, it is not possible to guarantee the safety of road tunnel users and an acceptable tunnel life cycle cost.

Operation and maintenance activities can be divided into three main streams of activity:

Efficient operations and a cooperative environment among different stakeholders in charge of tunnel and emergency management clearly underpin the safety and comfort of users and operators both in normal operations and in the event of an incident.

In Europe, Directive 2004/54/CE on "Minimum safety requirements for tunnels in the trans-European road network" clearly states that safety is not only related to structural elements and equipment. This European directive identifies and describes the specific roles and responsibilities for the different entities involved in operation and maintenance activities for a road tunnel..

The present chapter is broken down into four sub-sections:

In order to successfully and efficiently operate and manage a road tunnel, operational tasks and the responsible body for carrying them out, need to be established in order to ensure that all actions required are handled in a consistent and safe way (see page on Operational tasks). The level of safety provided for tunnel users is highly dependent upon the specific characteristics of the tunnel, but it also depends strongly on operational procedures and the people who are in charge of the tunnel.

The people in charge do not necessarily need to belong to the same organisation: stakeholders and roles can be quite different. For example, the traffic police are normally in charge of traffic, but the task is sometimes carried out by a road administration, and in some cases, several tasks are entrusted to a private company/operator. Moreover, the same task (for example: traffic management) can be performed by many different bodies (operating staff, police, subcontractor), so the relative roles and responsibilities have to be specified as well as recommendations to improve the behaviour of people involved in tunnel operation and their level of cooperation (see page on Stakeholder cooperation).

In each case, the organisation of the operation and coordination with all the different bodies must be defined by written procedures and protocols that are simple and straightforward, so that they are clearly understood by all parties and are robust under pressure in emergency situations.

The organisation of operation can be quite different from one tunnel to another; consequently it is difficult to define an overall common framework. However, it is convenient to assess for each tunnel or group of tunnels the most suitable organisation to be adopted both during standard operation and in the event of an emergency situation (see page on Organisation of operations).

Specific organisational and operational procedures are often required for complex tunnels and underground road networks. The following types of tunnels may be considered as “complex”:

All the above-mentioned infrastructures share several similar characteristics:

More information on such infrastructures, with specific case studies, can be found in the PIARC technical report 2016R19EN Road Tunnels: Complex Underground Road Networks.

Moreover, it is essential to establish standard operating procedures as well as minimum operating conditions and emergency plans. This is in fact a key step in planning the operational response to possible tunnel emergencies for which there need to be appropriate specific responses to various types of incidents (see page on Operating procedures).

Ventilation strategies must also be defined from the design stage. Different strategies are possible. The longitudinal strategy consists in creating a longitudinal air flow in the tunnel, in order to push all the smoke produced by a burning vehicle onto one side of the fire. If users are present on that side, they may be affected by the toxic gases and reduced visibility, so the use of this strategy in bidirectional and/or congested tunnels requires great caution. The minimum air velocity for successful smoke control depends on the design fire size and tunnel geometry (slope, cross-sectional area).

The transverse strategy takes advantage of the buoyancy of fire smoke: smoke tends to concentrate in the upper part of the tunnel space, from where it can be mechanically extracted. The system is designed so as to preserve a fresh air layer in the lower part of the cross-section (correct visibility, low toxicity) which allows self-evacuation. It is therefore important to keep the longitudinal air flow as low as possible in the fire region to avoid de-stratification and excessive longitudinal spread of smoke. This strategy is applicable to any tunnel, but the design, construction and operation of the system are more difficult and expensive.

The choice of ventilation strategy is generally guided by fire safety considerations (see chapter 5 of report 05.05.B 1999 "Ventilation for fire and smoke control"

The management and day-to-day operation, as well as the maintenance of a tunnel, involve high operational costs and funding requirements. In fact, tunnels are among the most costly parts of a road network to be operated (in terms of energy requirements, staffing and monitoring). The definition and optimisation of the different cost elements in a tunnel and appropriate recommendations to reduce them have been analysed by the PIARC tunnel committee. The efficient use of energy and the progressive reduction of energy consumption should be considered, with a view to delivering a sustainable operation of the road network (see page on Operational costs).

The final objective is clearly to guarantee an appropriate level of service and quality to the users. The achievement of this objective obviously depends on the nature and overall performance of the facilities and equipment. The performance of the equipment often depends on how this equipment is operated by the tunnel staff in terms of timeliness and appropriateness. Therefore the staff called to perform operational tasks must be well selected when recruited, well trained before starting their tasks and continually throughout their careers (see page on Staff-related issues).

The safety level and the traffic capacity in a tunnel are influenced by changes characterising the road network and the evolution of the traffic itself. The tunnel operator may occasionally need to make minor or major changes to the system or to the management criteria to cope with these changes. It is therefore necessary to monitor changes and accidents using information and feedback, to continuously and systematically improve tunnel operations.

The operator needs to receive feedback from actual operation experiences, which can be analysed and used to propose improvements (see page on Incident Feedback).

When the tunnel equipment no longer satisfies the needs of the operator, the requirements of legislation or when the nature or the level of traffic changes, it may be necessary to upgrade or refurbish the tunnel. For the refurbishment of an existing tunnel, recommendations mainly concerning measures to facilitate the management of the traffic network. Equipment reliability and durability and whole life costs also need to be defined (see page on Maintenance and Refurbishment).

The present chapter essentially concerns tunnels of medium to long lengths, with medium or heavy traffic volume, located in places where prompt external emergency interventions are possible. These tunnels are operated with a specific organisation, dedicated to one tunnel or a group of tunnels, which are part of the same road network.

The page Short / Low traffic tunnels presents the specific conditions concerning short tunnels, or tunnels with very low traffic, or scattered tunnels situated in areas with low population densities.

Generally speaking, tunnels are considered to provide a suitable or even higher level of safety the the open road network, Nevertheless, the potential consequences of incidents (breakdown, accident or fire) may be far more serious in tunnels than in the open air. Moreover, as tunnels are very often obligatory crossing points and are sometimes bottlenecks on the network, each total or partial closure can lead to major traffic disruptions or can oblige users to travel long distances on alternative routes.

For these reasons, operators and road authorities have to ensure the operational continuity and safety of road tunnels. They must guarantee to the users crossing the tunnel a level of service quality and safety complying strictly with regulatory requirements in force.

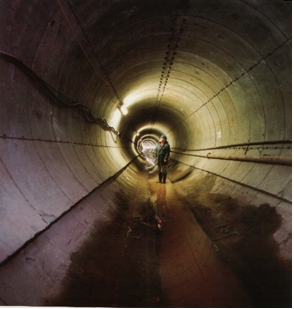

Figure 1: Maintenance works in a tunnel (France)

Depending on national regulations, tunnel operators and/or traffic police have to manage the traffic in tunnels (and on the route where the tunnel is located). In particular, they need to cater for the safety of users and any staff who may be working inside the tunnel (operating staff, sub-contractors, etc.). In several countries, the traffic police are in overall charge of traffic management and traffic patrolling, while the operator is in charge of operational tasks such as maintenance, operation of tunnel equipment, traffic surveillance and traffic assistance.

Generally speaking, typical tasks for the operators are:

Traffic surveillance and operation of tunnel equipment

Major tunnels (in terms of length, traffic density and complexity of the tunnel) are usually managed from a Traffic Control Centre. Very often, the Control Centre is equipped with remote surveillance systems (e.g. closed circuit television, automatic incident detection) and can remotely control certain equipment (ventilation, signalling, tunnel closure barriers, etc.).

Traffic Patrols

In certain cases, the operator can also deploy patrols that can provide a direct surveillance of tunnel users. These patrols can intervene very rapidly in case of need.

Management of civil engineering works

Civil engineering works in the tunnel undergo regular inspections. There is also regular maintenance of facilities such as drainage systems, gutters and all secondary structures (premises inside the tunnel, technical rooms, etc.),

Management of equipment

In major tunnels, the operator deploys several types of equipment that in the operation phase are under its own control. Tunnels are also equipped with systems that allow the operator to monitor the status of equipment. The operator must cater for the maintenance of equipment fitted in the tunnel. Here again, it is possible to have access to computerised tools to assist in performing this task.

Management of emergency situations

Whatever the nature of the incident, whether it is a problem related to traffic (accident, interlinked accidents, fire, etc.) or to equipment (loss of power supply, malfunctioning of data transmission network, etc.), to intervene or to inform/activate the pertinent service/authority is the standard duty of the operator in charge of the surveillance.

Technical and Administrative management

In addition to tasks directly related to tunnel operation, the operator provides the technical and administrative services supporting the management of the infrastructure and, of course, the personnel. The operator caters for the design of any equipment upgrading, the direction of the works, the investment and operational budgets for the proper functioning of the tunnel. Lastly, the operator also develops statistics and monitors the achievement of its own objectives by preparing periodical reports on the operation of the tunnel/route (financial indicators, traffic indicators, etc.).

The Technical report 05.13.B "Good Practice for the Operation and Maintenance of Road Tunnels" deals with this subject in parts 2 and 4.

The management of road transport is a very complex task. It is even more complex within a tunnel environment. Part of this complexity is due to the fact that skills and competencies required for the management of tunnels are scattered among different services. The cooperation of the different stakeholders is clearly a vital pre-requisite for effective traffic and incident management.

Figure 1: Fire services, tunnel operator staff and authorities during a safety exercise

The Technical Report 2007R04 "Guide for organizing, recruiting and training road tunnel operating staff" defines the organisational tasks in a more precise manner.

Although the organisation of tunnel operations varies from one country to another, generally it involves the following groups:

In a few cases, emergency rescue services are considered as part of the operating staff.

In some cases, a single organisation can be responsible for all the personnel required for tunnel operations. In other cases, operations may be shared by several public and private organisations. For example, the tunnel owner or the road administration may entrust a public or private organization with operation as a whole and then contract out specific operational tasks (e.g. maintenance tasks).

Incident management measures depend on national regulations and local requirements specific to each tunnel. Consequently, the organization of the operator and the traffic police depends on the local context.

Technical Report 2007R04 defines the organisation of operation in greater detail in chapter 4 "Operating staff: tasks and facilities".

The operation of complex tunnels and underground networks must take into account specific factors and in particular:

The volume of traffic is generally a more significant factor and in high traffic volume conditions traffic congestion is much more frequent. It follows that the number of persons in the tunnel is much higher and in the event of an incident, the number of users to evacuate will be more significant.

Ramp merge and diverge areas are important locations in terms of risk of accidents.

The assumption, which is sometimes prevalent from the start of projects, that there will never be a traffic blockage must be analysed with much circumspection. It is indeed possible to regulate the volume of traffic entering into an underground network in order to eliminate all risk of bottlenecks. Nevertheless, this leads to a significant decrease in the capacity of the infrastructure (in terms of traffic volume) which often goes against the reasoning that justifies its construction. Over time, measures of reducing entering traffic must be relaxed, or even abandoned because of the need to increase traffic capacity. The probability and recurrence of bottlenecks increase, disregarding the initial assumption upon which the network was based (particularly in terms of safety and ventilation during incidents).

Issues to take into account include:

Ventilation systems in complex tunnels and underground networks must take into account:

Communication with tunnel users must be reinforced and adapted throughout the multitude of branches within the network. Communication must be able to be differentiated between the different branches according to operational needs, especially in the case of fires.

Users must be able to identify their position inside the network, which would require, for example, the installation of specific signs, colour codes, etc.

Directional signs and prior information signs at interchanges or ramps must be subjected to careful consideration, particularly the visibility distances with regard to signals and the clear legibility of the signage.

Attention must be given to the interfaces and cooperation between stakeholders, notably for traffic management matters and safety matters (especially fire incidents), including evacuation of users and intervention of emergency response agencies in response to fire incidents.

A complex underground network is usually operated by numerous operators whose cultures, skills, objectives and organisations are multiple and often different. However, the safety conditions inside the network and the level of service provided to users require good coordination between all the operators, together with excellent mutual understanding and confidence.

A Coordination Committee with a strong leadership is therefore absolutely essential.

Control centres must take account of the interfaces within the network and between diverse operators. They must allow the transmission of common information which is essential to each operator, and facilitate the possible temporary hierarchy of one control centre over another. The architectural design of the network of control centres, and of their performance and methods, must be subjected to an overall analysis of organisations, responsibilities, challenges and risks. This analysis should reflect a range of operational conditions such as during normal and emergency scenarios and should review the interaction between the different subsections of the network and the respective responsibilities of each control centre.

The safety conditions of a complex underground network do not differ fundamentally to those of a standard tunnel. However, everything is more complex, due to:

Excellent knowledge of the networks and the conditions faced within the network during an emergency are therefore absolutely essential. Certain tools may be helpful, such as:

However, although these tools are necessary, they will never replace training and basic human factors such as the capacity for initiative and adaptation which remain fundamental for coping with a large-scale event.

Every tunnel operator produces and updates written procedures (sometimes called "Operating instructions") which define the objectives and criteria of possible actions by different internal service providers, which can affect the tunnel or road. All types of operational events need be taken into consideration for the procedures, including routine incidents, serious accidents and emergencies. The "Operating instructions" contain the basic actions to be carried out with associated procedures and existing constraints.

The operator's staff also needs an emergency plan for both intervention after a road accident and technical failure of equipment in the tunnel. This plan usually meets regulatory requirements and includes operational procedures and instructions involving, at minimum, the tunnel operators and the intervention personnel in case of an incident or technical failure. The emergency intervention procedures should be coordinated with those applied by emergency and rescue services. The detailed content of this plan could be defined by national instructions or directives specific to each country and needs to be tailored to the specific technical and organizational aspects of the tunnel.

Technical Report 2007R04 defines the organisation of operation in greater detail in chapter 4 "Operating staff: tasks and facilities"

The tunnel ventilation system should ensure adequate air quality during normal operation and maintenance activities, as well as providing the desired smoke management in case of fire. Moreover, the escape routes should be kept free from smoke.

However, when selecting and operating a ventilation system, normal operation and smoke management cannot be considered independently.

During normal operation, it is required to keep the pollutant level inside the tunnel below defined threshold values for visibility due to particulates, or toxic gases in each section of the tunnel. Some tunnel ventilation systems can be primarily designed and operated in order to minimize the impact on the environment at the tunnel portals. Further information on design criteria for normal operation can be found in the specific section of the page on "Design and dimensioning".

Control for normal operation should be achieved at minimal operating costs. It is conventional to control the operation of the ventilation system through measurement of the relevant pollutants (including opacity and either or both CO and NOx), to optimise the use of the system. In some cases, tunnel operators need to use SCADA systems to check the proper functioning of automatic control systems. For further information see the page on "Control and Monitoring".

Other objectives are occasionally pursued e.g. to minimise the risk of condensation occurring on the windscreens of vehicles and preventing the entrainment of fog from outside the tunnel. For maintenance work in the tunnel, the tunnel ventilation has to ensure the air-quality criteria for longer exposure of workers.

In case of a fire in a tunnel, the ventilation system must be operated in order to establish and maintain appropriate conditions for self-evacuation and rescue operations.

During the self-evacuation phase (also called the self-rescue phase, during which tunnels users would, of their own volition, attempt to evacuate from the tunnel), the ventilation system aims to create and maintain a tenable environment for the evacuation of tunnel users. Specifically, this environment consists of acceptable visibility and air quality levels.

During the fire-fighting phase, the ventilation system operation has to be decided by the head of emergency operations, who should choose the best solution taking into account the possibilities of the ventilation system and the operational needs of the firemen.

Further information can be found in section 8.3 "Operation of smoke control systems" of the PIARC report 2007 05.16 "Systems and equipment for fire and smoke control".

In contrast with normal operation, where conditions in the tunnel change rather slowly, the conditions during a fire may change rapidly, leading to deteriorating conditions within the tunnel. The designer initially defines the objectives of the ventilation system, sizes the necessary equipment and proposes what actions the operator should take under various scenarios. The designer, therefore, needs to understand the behaviour of the smoke, what the tunnel user might do (human behaviour), and what the operator, and later emergency services, should do in response to an emergency.

Different ventilation strategies may be used in tunnels. The choice between them is generally guided by fire safety considerations; the use of the system in normal operation is adjusted to suit.

The PIARC report 1999 05.05 "Fire and Smoke Control in Road Tunnels" provides extensive details on smoke management and PIARC report 2011 R02 "Road tunnels: Operational strategies for emergency ventilation" discusses different ventilation methodologies and operational strategies..

For tunnel operators this is reflected in a series of choices that can be made about the configuration of existing ventilation equipment. Usually these choices are based upon pre-planned equipment usage configurations, hence the following questions are to be considered:

The objectives of the design should provide a useful means of characterizing the potential operational performance of the ventilation system, whereas the actual characteristics of the system define the achievable result from an operational perspective. In responding to a real incident this distinction may be critical – and the importance of the design-operator interface crucial.

In addition, it is essential to establish standard operating procedures for road tunnel fires. The development of an integrated Emergency Response Plan is an essential first step in planning the operational responses to tunnel emergencies. The plan should specify particular responses to various types of incidents, including the description of how the ventilation system should be used. For its preparation, a proper coordination and interaction between the tunnel designers (in some cases), the tunnel operators, and all outside agencies that might ultimately become active responders to an emergency incident within the tunnel, is required.

In the case of urban or complex underground systems, tunnel operators have to face additional challenges: during normal operation to properly control the fresh air flow inside the tunnel and make sure that all branches can received the required amount of air for pollutant dilution; and in case of incidents with fire, to minimise the harmful effects of smoke by isolating different tunnel sections to avoid smoke contaminating the whole tunnel network.

Further information on main issues related to ventilation of these tunnels can be found in chapter 6 "Ventilation" of the report 2016 R19 "Road Tunnels: Complex Underground Road Networks".

Experience shows that a kilometre in a tunnel is always more costly than a kilometre of the same road outside. Underground structures require systems and equipment that ensure safe operation under normal operating conditions and allow the protection and the evacuation of users and the intervention of rescue services in case of an incident, accident or fire. These facilities not only involve considerable investment costs but also result in particularly high costs for operation and maintenance. Thereby the role of the operator is to ensure the continuity and the safety of operation in a context of controlled costs.

In all cases, even a high standard of tunnel operation may not allow an optimisation of operational costs, if the design and the construction of the tunnel have been undertaken to a low quality level. Operational costs therefore need to be a major consideration during the different phases of the project and the work execution. Solutions need to be found well before becoming an issue during the operational phase.

Operational activities have to be organised at an adequate level in order to ensure that the expected lifecycle of the equipment is met, without compromising mandatory operational performance requirements. The lifecycle of equipment in tunnels is normally shorter than in other environments, since the atmosphere in tunnels is particularly corrosive.

The Technical Report 05.06.B "Road Tunnels: reduction of Operating Costs" is entirely devoted to operating costs and in particular focuses on how to reduce them.

Tasks entrusted to the operating staff are essential for safety and the overall efficiency of tunnel operation. Moreover, the context is evolving, with operational issues growing in importance and operating systems becoming increasingly complex.

Figure 1: Operating staff in a tunnel control centre (Spain)

The staff in charge of tunnel operation therefore need to satisfy the following requirements:

During recruitment phases, the qualifications required for the future operators must be defined according to the nature of operational tasks. Even if the tasks are similar in all countries, the people responsible for executing them do not necessarily belong to the same kind of organisation in each country. Nevertheless, the skills and aptitudes required should be similar.

While designing the staff training (initial or permanent), the following two issues need to be addressed:

If there are no national rules on the content of training, the operating body has to adapt its training programme to the specific characteristics and requirements of its tunnels.

The Technical Report 2007R04 "Guide for organizing, recruiting and training road tunnel operating staff" specifies the recruitment and training of personnel in greater detail, chapters 7 "Recruitment of operation staff" and 8 "Training operating staff" .

The operator needs to regularly test procedures and the efficiency of personnel, making sure that staff are familiar with the different equipment installed in the tunnel. Any possible deficiencies in the execution of specific tasks can thus be detected.

In addition to internal exercises, the operator and emergency services need to organise joint rescue exercises with the participation of the traffic police, the operator, medical services and the fire and rescue services. The results of each exercise should be analysed. If lessons drawn from an exercise reveal any shortfalls, the intervention strategies should be reviewed.

For road tunnels, exercises should be regarded as an integral part of the tunnel emergency planning process. In many countries, road tunnel safety regulations specify the time intervals between emergency exercises and sometimes give some indication about the contents of the exercises.

For tunnel operators, organising such exercises represents a considerable task.

The collection of data regarding incidents and accidents and their analysis is essential both for the evaluation of the operation criteria and for the assessment of risks in the tunnel. All of this is important with a view to a continuous improvement in tunnel safety. In particular, the collected data enable the frequency of events to be evaluated. Data also provide feedback regarding the consequences of events and also the effectiveness of safety measures and equipment. They also provide additional information on the real behaviour of tunnel users.

The collection and analysis of data regarding incidents and accidents should allow the following two objectives to be achieved:

Lastly, they provide information (national statistics according to the type of tunnel) that is useful for the analysis of risks relating tunnels that are in project stage (ie. in development) or tunnels under operation that do not yet have an adequate database.

The lessons drawn from the operation, particularly during incidents and accidents, should be analysed. In fact if the results of these analyses reveal deficiencies, there is an opportunity to intervene by improving strategies and/or operating instructions.

The Chapter 3 "Collection and analysis of data on road tunnel incidents" of Technical Report 2009R08 defines in detail the conditions for analysing data from incidents and/or accidents.

Figure 1: Maintenance tasks carried out on tunnel lighting

Chapter 2 of technical report 2008R15 "Operation of existing urban road tunnels" defines the conditions for carrying out maintenance when the tunnel is in operation.

The same difficulties as those mentioned above are likely to be encountered during a refurbishment of equipment in a tunnel that cannot be closed down easily. With regard to maintenance interventions, this type of works may require several weeks, or even several months to be completed. Consequently, more elaborate (and often costlier) measures have to be planned.

Chapter 6 of technical report 05.13.B "Renovation of tunnels" discusses aspects relating to refurbishment.

Fig 1 : Short tunnel with lighting in rural area

For these particular tunnels, it is recommended to carry out a detailed specific analysis for each tunnel (or group of tunnels located on the same road network), taking into account:

This analysis will then make it possible to organise and to implement the most suitable operating system, according to the specific conditions of these tunnels.

This chapter gives information on the general principles of maintenance, technical inspections and life cycles. Some information related to complex tunnels, civil works and winter maintenance is also given.

Structural elements and the technical equipment need regular maintenance, the aim of which is to ensure safe driving conditions for the public by keeping the tunnel at its designed safety standard (see page on Maintenance of equipment). General recommendations for maintenance in tunnels are defined as well as the specific features and their facilities.

Life cycle or Life Cycle Cost (LCC) aspects are becoming increasingly important. From an economic point of view, it is important to consider these aspects both in the design and in the operation of tunnel equipment (see page on Life cycle of tunnel equipment).

It is important to verify that the maintenance actions conducted have enabled the pre-defined objectives to be achieved. These verifications take the form of technical inspections, their aim being to make sure that the maintenance actions carried out allow the equipment to function in a satisfactory manner and that the frequency of maintenance actions is adequate (see page on Technical inspections).

The technical report Good Practices in Maintenance and Traffic Operation of Heavily Trafficked Urban Road Tunnels - Collection of Case Studies provides a collection of case studies to gather, evaluate and comment on international expertise related to maintenance and traffic management in highly trafficked urban road tunnels. A large number of cases provided an insight into the implementation of these special requirements for urban road tunnels.

Although maintenance actions on a “Complex underground road network” are essentially similar to those on a typical road tunnel, they are more complex due to:

The special recommendations concerning the maintenance of an "underground road network" are presented on the page "Maintenance of complex tunnels“.

In some countries, and not only in mountainous areas but also in very cold areas, winter maintenance can be quite a challenge in maintaining the tunnel functional and safe or in implementing new electronical and mechanical equipment’s and technologies (see the page on Winter maintenance)

Civil engineering structures within the tunnel also need regular monitoring and inspections. It is necessary to carry out regular maintenance of facilities such as drainage systems, gutters and all secondary structures (premises inside the tunnel, technical rooms, etc.), For further information, please consult the page on “Civil Works”.

Throughout the life of the tunnel, the operator should carry out both the maintenance of civil engineering works and the tunnel equipment. (See Report 05.13BEN "Good Practice for the Opereation and Maintenance of Roads Tunnels"). The maintenance of civil engineering structures is not described in this paragraph.

The maintenance operations on equipment can be classified into two groups:

It is recommended to use preventive maintenance where possible and for those systems that are not redundant and are related to safety. Preventive maintenance allows the joint planning of different maintenance tasks in the event of every closure of the tunnel to traffic. Moreover, it helps maintain the equipment in a good operating condition. It may be noted however that even when preventive maintenance is carried out very well, the operator cannot avoid corrective interventions. However, preventive maintenance will ensure costly corrective maintenance is kept to a minimum.

Usually the operator's staff do not carry out all maintenance tasks; the operator normally entrusts contractors and several options are consequently available:

Chapter 7 of Technical Report 05.06.B entitled "Cost of maintenance", chapter 4 of Technical report 05.13.B entitled "Maintenance and operation" and chapter 6 of Technical Report 2007R04 entitled "Organising operating staff", give more complete information on the subject of maintenance.

If they exceed a few hundred meters in length, road tunnels are to be provided with equipment for ensuring the safety of users under normal conditions or in case of disruptions to normal operation. Because of their involvement in the global safety chain of the tunnel, this equipment must be selected and designed with great care, with regard to maintenance, inspection and refurbishment. Hence a report has been produced to assist the operator or operating body with the issue of maintenance and technical inspection.

The technical report 2012R12EN entitled "Recommendations on management of maintenance and technical inspection of road tunnels" gives recommendations for the management of maintenance, essentially in the domain of equipment. The aspects relating to light civil engineering are listed and described only very briefly.

Life Cycle Cost (LCC) aspects have become an important issue for private tunnel owners, as well as government agencies. Sound knowledge of life cycles helps to optimise investment costs during the early stages of designing a system. It is also helpful in organizing the periodical maintenance of technical equipment. The technical report 2012R14EN entitled "Life cycle aspects of electrical road tunnel equipment" outlines how LCC aspects support the design of equipment as well as maintenance concepts. Bearing in mind that investment decisions are often technology-driven and that equipment costs have risen dramatically in the past years, the report helps to understand the life cycle process and the aging process of material. The report provides background knowledge on LCC aspects, which could be of use for further investigations. Specific focus is given to the surrounding ambient conditions, e.g. temperatures, which have a significant impact on the aging process.

The increasing variety of tunnel equipment means that life cycles may vary considerably from one type of equipment to another.

Some equipment may have a lifespan of more than 20 years (power supply, ventilation ...); others will only last a decade or so (notably equipment with a lot of electronics). For some, its lifespan may even be less than 10 years.

It is therefore essential to examine the lifespan of each family of equipment, with particular attention when this lifespan is low (10 years or less). The purpose of this review is to identify the factors that have a strong influence and that can be acted upon to ensure the lifespan of the product, or even improve it.

It is particularly useful to take into account factors such as temperature, humidity, mechanical stress and the environment.

A life cycle analysis can be conducted at different stages of the life of a tunnel (and its equipment):

Technical reports 2016R01 “Best practice for life cycle analysis for tunnel equipment” and 2012R14 “Life cycle aspects of electrical road tunnel equipment” provide further information on this issue.

The equipment of a tunnel is highly varied. From electromechanical equipment (power supply, ventilation, lighting ...), to operating equipment using more recent technologies (video surveillance, SCADA, automatic incident detection...), it requires more or less frequent interventions to maintain functionalities.

Interventions to be performed on equipment can be grouped into three broad categories:

Maintenance can be defined as a set of actions that maintain equipment in a specified state, restore it to this state or ensure that it can provide a specific service. These actions can be preventive in nature (referred to as preventive maintenance) or remedial (corrective maintenance).

Maintenance control, in the broadest sense, aims at ensuring that the maintenance actions carried out allow satisfactory operation of the equipment and that the financial resources allocated are adapted to requirements.

An assessment can be carried out by conducting technical inspections at specified periods:

The initial inspection must be carried out before equipment is put into operation. It aims, on the one hand, to check the quality and performance of the installations and, on the other hand, to ensure that the tunnel and its equipment comply with regulations, in particular with regard to safety.

The initial inspection, which provides a reference on the condition and performance of the tunnel at commissioning, should be followed by further inspections throughout the tunnel’s life. These inspections must be carried out periodically at an interval that may vary from one country to another, but which is, in most cases, of the order of several years.

The results obtained during these various inspections therefore make it possible to verify that maintenance is well adapted and that the expenditure and financial budget makes it possible to achieve the objectives set.

When the equipment approaches the end of its life, these inspections also enable refurbishment or renewal actions to be planned.

Further information on technical inspections can be found in technical report 2012R12EN: Recommendations on management of maintenance and technical inspection of road tunnels.

1. Responsibility of each operator

2. Commitment of each operator in the context of the overall maintenance strategy

3. Coordination between the Operators

Maintenance in complex tunnels is a holistic and interrelated issue where a contribution of one sector must be proactively complemented by the contribution of other sectors. The purpose of maintenance in underground and complex tunnel structures is to improve the serviceability of the infrastructure and to reduce operational costs. When maintenance is performed at the time of the tunnel life cycle it optimises the available equipment, minimises the risk of accidents and largely contributes to public safety. Tunnel operators, particularly those involved in the maintenance of large underground and interconnected infrastructures are reminded of the need to optimise their maintenance strategies and to enhance public confidence in the use of these infrastructures by making them safer, efficient and continuously available for use.

The strategic components related to maintenance in tunnel networks may be divided into four categories:

Each operator is responsible for the safety level of its infrastructure, which contributes to the overall level of safety of the entire complex. Each operator is responsible for informing the lead operator of its maintenance demands and the demands of the others. A global maintenance coordination plan should be established among all operators and adjusted to the individual operators. Focus should be on global benefits and minimizing the time of restricted tunnel operations is essential.

At same time, each operator has responsibilities that may be impacted by actions of other operators. The Lead Operator of the underground tunnel infrastructure is responsible for the overall co-ordination and communication process.

Each operator is responsible for managing and maintaining its own equipment. Each operator must establish the list of equipment under its responsibility and share it with the other operators.

Some equipment could be considered as strategic equipment, necessitating collective responsibilities. The list of this strategic equipment must be established, discussed and shared. It has also to be clearly defined who is in charge of what.

It is crucial to acknowledge that the collective efforts of operators will trigger combined responsibilities for all participants in the process.

The coordination process in the context of the underground interconnected complex tunnels entails the following:

a) Organizational Behaviour

There is a need to develop group work which is only achievable if the organisational behaviour is aligned to the needs of the infrastructure (refer to Operation of complex tunnels).

b) Maintenance of one has implications on the others

Best practices in tunnel maintenance will also require a coherent effort from the key players and stakeholders. This can be achieved by defining a set of principles and procedures set out in the operator’s procedure manual generally known as the inventory manual. Tunnel operators are encouraged to be acquainted with all key components of the inventory manual which are applicable to their functions and have been developed by PIARC over many years.

Fig 1. Snowstorm at the entrance of the Somport tunnel (Spain)

The considerations that impact the winter serviceability of road tunnels are both numerous and varied. The operator, whose mission is to ensure user safety, must therefore make every effort to counter the adverse effects of winter as well as ensure that users benefit from safe conditions in circumstances that are sometimes very difficult, such as extreme weather events. The operator must adequately coordinate its tunnel de-icing and snow-clearing teams, which can be challenging and slow in busy traffic. Visibility in tunnels further decreases during the winter months, as lighting fixtures become dirty and due to the spray deposits along the walls, which also affect surveillance cameras and air quality sensors. The operator must assure the operational availability of all safety and fire protection equipment, which must also be protected from freezing.

Fig. 2: Snow clearing of the Viger tunnel without traffic disruption – Montreal Quebec (Canada)Operational continuity is of the utmost importance for the operator. However, according to the nature of the problems experienced in winter, any major event forcing a closure or a reduction in operations will inevitably have repercussions on the entire network, resulting in socioeconomic costs related to delays and user complaints. More so than any other season, winter compromises operational continuity. A sound management of the network is therefore essential.

Communications make it possible to transmit information in order to facilitate the management of difficult situations. At all times, the operator must provide useful information to the media in order to quickly inform users of road conditions, closures and snow removal operations. In a transport organisation, efficient communications structured in a well-defined decision-making hierarchy make it possible to effectively manage extreme weather events that require major decisions, such as lane or tunnel closures, whether for safety reasons or de-icing operations.

Table 1 below presents a list of the particular problems inherent to the winter conditions that road tunnel operators must face. It also presents a non-exhaustive list of preventive and corrective actions, in addition to the usual constraints that operators must deal with when conducting operations.

| Problem | Preventive actions | Corrective maintenance | Constraints |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Water infiltration |

- Program to identify and seal leaks and infiltration - Monitor waterproof joints |

- Manage infiltrations - Install heated temporary pipes - Repair waterproof joints

|

- Maintaining traffic flow - Heavy traffic periods - Permit to close lanes temporarily for maintenance (closures usually at night or on weekends) - Difficult work conditions in road tunnels |

|

Formation of icicles or stalactites |

Locate icicles and stalactites and conduct de-icing operations as needed when user safety is compromised |

- Availability of snow removal teams and equipment - Heavy traffic periods - Permit to close lanes temporarily for maintenance - Difficult work conditions in road tunnels |

|

|

Frost or snow on the roadway - Unexpected slippery conditions in road tunnels - Motor vehicles and heavy vehicles have difficulty exiting tunnels during snowstorms, causing traffic slowdowns, traffic jams and accidents - Risk of skidding in sloped accesses, causing motorists to lose control, accidents |

- Inspection of snow removal equipment after use and before storage - Application of de-icing agents when precipitations begin - Installation and use of roadway de-icing systems (heating cables, hydronic heating, etc.) at tunnel - Predictive diagnostics to preheat equipment that is sensitive to extreme cold |

Remove and transport snow and apply de-icing agents (abrasives are to be avoided as they can block drain pipes) |

- Budget - Availability of snow removal teams and equipment (24/7) - Heavy traffic periods - Permit to close lanes temporarily for maintenance - Restrictions on the use of de-icing agents (environmental impact, toxicity, storage and application precautions, recovery, transport and destruction) - Efficiency of de-icing agents relative to temperature - Risk of damage to the concrete structure caused by de-icing agents (e.g. salt). |

|

Debris and formation of ice in drain pipes |

- Periodic inspection program - Clean pipes, bore holes as needed - Verify the operation of heating cables - Monitor low temperature alarms in protected systems |

- Flush pipes - Remove ice in gutters - Bore holes in pipes as needed - Replace defective drainage components |

- Maintaining traffic flow - Heavy traffic periods - Permit to close lanes temporarily for maintenance (closures usually at night or on weekends) - Difficult work conditions in road tunnels |

|

Accumulation of dirt on tunnel walls, ceiling and equipment, such as surveillance cameras, lighting fixtures, air quality sensors, signalling equipment, escape route indicators, etc. |

- Visual inspections - Maintenance operations, including cleaning surveillance cameras, walls and lighting fixtures outside busy traffic hours |

Maintenance operations, including cleaning surveillance cameras, walls and lighting fixtures outside busy traffic hours |

- Low temperatures - Heavy traffic periods - Permit to close lanes temporarily for maintenance - Restrictions on the use of cleaning products (environmental impact, toxicity, storage and application precautions, recovery, transport and destruction) - Efficiency of cleaning products relative to temperature - Difficult work conditions in road tunnels |

|

Corrosion of doors, anchors, equipment, cable and equipment mounts |

- Use of products and materials that are compatible with the aggressive environment in tunnels - Periodic inspection program - Use of stainless steel or composite components where applicable - Inspection and maintenance operations, including lubrification and/or rust protection |

Replace rusted components and equipment as needed |

- Standards applicable to road tunnels - Resistance to fire, water, humid and corrosive environments |

|

Cracking, fragmentation of concrete debris falling on the roadway, heaving of concrete slabs, contamination of concrete |

- Waterproof membranes - Protective coatings - Periodic inspection program with damage and contamination surveys - Surface repairs |

Repair the concrete Seal cracks Rehabilitate the infrastructure |

Budget Permit to close temporarily for inspections Maintaining traffic flow during work Degraded modes of operation Measures to reduce impact on users Difficult work conditions in road tunnels |

|

Increased energy consumption during winter, peak power demand and impact on the electricity network Uneven between seasons and impact on billing |

- Analyse and follow up energy consumption and peak power demand - Intelligent energy management system and measures to reduce demand - Selection of energy-efficient equipment - Use of alternative energy sources where possible and cost-effective - Storage of energy during low consumption periods to balance energy use - Technological watch |

- Budget and cost-effectiveness of performance-enhancing solutions - Availability of space for required equipment (e.g. storage) - Availability of alternative energy sources - Resistance to changing operational and energy consumption habits - Laws, regulations, political pressure, sustainable development |

|

|

Erratic operation of electronic equipment due to cold and humidity |

- Use of products that are compatible with the cold, humid and aggressive environment in tunnels - Monitor alarms - Periodic operational tests and calibration |

- Permit to close temporarily for inspections - Maintaining traffic flow during work - Degraded modes of operation - Measures to reduce impact on users - Difficult work conditions in tunnels |

|

Usually, the construction of roads through mountain ranges may require tunnels at high altitudes. Above 1.000 meters over sea level, special maintenance activities are required to provide acceptable traffic conditions inspite of the risk of snow or ice formation. This situation becomes critical in the proximity of tunnel portals.

At the north of the province of Huesca, in Spain, where several tunnels above 1.100 meters above sea level can be found, several important factors are to be considered to deal with temperatures which can go below -20ºC.

Water is the hardest enemy to fight: causing infiltration due to low temperatures, producing cracks and even spalling in vaults and side walls.

At the tunnel portal, an adequate construction of pavement and good quality of road painting are key factors for their durability. High quality materials are required because snow plough circulation and extreme meteorological conditions can cause their deterioration.

To fulfil the requirements of Rd635/2006, the transposition to the Spanish law of the European Directive 2004/54 on minimum requirements for road tunnels safety, several types of equipment must be installed which can be severely affected by malfunctioning or even breakdowns when needed.

Suspended power supply lines are exposed to ice formation which is the origin of outages which, if regular, can affect the durability of UPS and diesel generators.

Water tanks to supply fire hoses of the tunnel must be carefully constructed to avoid the appearance of cracks. In addition, continuous water circulation is advisable.

Water supply pipes must be protected with thermal protection and, if possible, emptied. Opening elements of fire hydrant and hoses can be also affected and the technical rooms containing pumping machinery should be above 0ºC.

In addition, proper maintenance of the vehicles used for operational and emergency purposes is crucial, including the use of adequate antifreeze products for motor and fuel and water tank protection.

And last but nor least, both the difficulties in the relief of the operation staff and appropriate clothing (not only warming or waterproof aspects but also visibility improvement) must be considered.

When the tunnel equipment no longer fulfils the needs of the operator or the tunnel users or when the requirements of legislation or the characteristic of the traffic has changed, it may be necessary to upgrade the tunnel.

The need for pre-planned work can be the consequence of, for instance, new regulations or opportunities to improve equipment, its functionality, safety or energy-efficiency, or to reduce preventive maintenance requirements. There may be a further occasional need to replace equipment due to age deterioration. Major work will usually be treated as special projects.

Activities may include:

This chapter of the Manual is broken down into six pages:

Due to the amount of technical equipment in an urban road tunnel it is of utmost importance to keep all documentation about the equipment up to date, not only after major refurbishments, but whenever a change is made.

A refurbishment usually requires updating documentation of:

When planning a major refurbishment it is recommended to use the same approach as for a new design.

General recommendations on refurbishment can be found in the PIARC Report 2008R15EN "Urban road tunnels : recommendations to managers and operating bodies for design, management,operation and maintenance".

If the tunnel design and equipment no longer fulfil the requirements of the operator, the tunnel users or legislation, it may be necessary to refurbish and/or upgrade the tunnel.

During refurbishment or upgrading, it is important to:

Safety of both workers and tunnel users can be influenced by completing refurbishment/upgrading activities in the shortest period possible and every effort should be made to avoid delays in the progress of work. Well planned and efficiently implemented works can effectively reduce the length of these periods.

For both tunnel users and workers, total closure of all tunnel tubes during refurbishment/upgrading obviously provides a much higher level of safety. Workers are protected from traffic and teams can work on all facilities throughout the full length of the tunnel. For traffic, accident risks linked to the implementation of temporary traffic control measures within the tunnel are avoided.

In certain cases it is impossible to close the tunnel entirely. For instance, if the tunnel is the only reasonable means of crossing a strait or a mountain ridge, where alternative routes are not possible, not practicable or very expensive. In these cases refurbishment/upgrading of structures and installations have to be performed while the tunnel remains in service.

Partial closure of one or more lanes is possible during refurbishment/upgrading activities, but working in a tunnel while traffic is present is dangerous for the personnel and requires specific measures to protect them (e.g. the construction of temporary barriers to separate workers from the traffic).

In twin-tube tunnels, one tube can be closed for refurbishment while bi-directional traffic flow is allowed in the other tube. However, this solution is far from ideal and should only be adopted if it is not possible to divert traffic onto an alternative route. Whilst it obviously protects the safety of workers, this situation leads to the users driving in opposing directions within a tube where they are accustomed to traffic moving in only one direction. This can induce a potential increase in accident rates and should be avoided in heavily trafficked tunnels. In tunnels with low to moderate traffic, the risk of accidents can be reduced by the use of VMS and overhead lane control signs. In the case of three-lane tubes, the centre lane should, if possible, be kept free of traffic and act as a buffer safety zone.

In all cases where there are plans to alter the usual traffic configuration in a tunnel, additional safety measures should be implemented: reduced speed limit, closure of slip roads in the vicinity of the tunnel and the implementation of safety exercises in collaboration with emergency services under similar “works” conditions.

Finally, each time the lane/tube/tunnel is reopened to traffic following a closure, great attention must to be given to clearing and cleaning the road to prevent accidents caused by tools and materials in the tunnel or on the road. Similarly, any temporary or uncompleted works must be satisfactorily secured and made safe for the following operating period.

Additional information on refurbishment/upgrading can be found in chapter 6 "Renovation of tunnels" of technical report 05.13.B.

Tunnel refurbishment/upgrading should be conducted in such a way that the negative impact on the environment is as low as reasonably practicable. This can be obtained by:

Tunnel refurbishment/upgrading can in many cases provide an opportunity to improve the environmental impact of the infrastructure as a whole, either through changes to the tunnel’s design or to its equipment.

In terms of design, an example of a major refurbishment project conducted with environmental issues in mind is the Croix Rouse tunnel in Lyon (France). In order to upgrade the tunnel’s safety standards, the initial tube has been linked to a new parallel escape gallery via cross-passages every 150 metres, thereby enabling the evacuation of users. The tunnel owner wished to give additional functions to this escape gallery by allowing its use by public transport (buses) and environmentally-friendly modes such as pedestrians and cyclists. This is an interesting example of the sustainable use of infrastructure for purposes other than those for which it was initially intended.

In terms of tunnel equipment, refurbishment/upgrading can provide an opportunity to reduce energy consumption. The main energy-consuming families of equipment in a tunnel during normal operation are lighting, ventilation, safety devices (signalling, closed circuit television CCTV, etc.) and pumping facilities (in subsea tunnels or when there is water seepage). The respective share of each of these energy-consuming systems varies greatly, depending on the specific characteristics of the tunnel: length, gradient, water ingress, etc. In terms of optimization during refurbishment/upgrading, lighting and ventilation systems are those which provide the highest potential energy savings.

Actions taken on lighting during refurbishment/upgrading are primarily designed to better define the lighting requirements in the entrance zone, which is the most heavily lit. Solutions implemented may:

Other actions may concern the optimization of interior zone lighting. At the moment, most experiments, and in some cases test sites, involve the use of LEDs (light emitting diode) sources.

An example of energy-saving measures implemented to ventilation during refurbishment/upgrading is the installation of jet fans with inclined outlets. It has been shown that these jet fans can enable a significant improvement in the in-tunnel thrust obtained and a reduction in energy consumption.

Outside air quality (at tunnel portals or vitiated air extraction systems) can be improved during refurbishment/upgrading, through increased stack heights or by the installation of vitiated air treatment systems (air cleaning systems). In some countries, vitiated air treatment systems have been put in place (Spain, Japan, Italy, Norway France….). However, after some years of use, the conclusions regarding the efficiency of air cleaning are different from one country to another. The decision to use such systems therefore has to be carefully analysed, taking into account several criteria (investment costs, efficiency, maintenance, etc.).

Finally, tunnel refurbishment or upgrading can provide an opportunity to assist in the preservation of the animal species living around the tunnel. Measures that can be implemented include restoring passageways for certain species or preserving reproduction areas.

General environmental questions related to the design, construction, operation and refurbishment of tunnels are dealt with in the technical report 2017R02EN “Road tunnel operations: First steps towards a sustainable approach”.

Questions relating to the tunnel impact on outside air quality are dealt with in report Technical Report 2008 R04 "Road Tunnels: A Guide to Optimizing the Air Quality Impact upon the Environment".

Tunnel refurbishment or upgrading may require:

If possible, total closure of the tunnel for refurbishment/upgrading is strongly recommended during the entire duration of the works as it undeniably provides the best solution in terms of safety for both workers and users. When possible, it is better to implement closures over short periods and during low traffic (night, weekends etc.).

However, these two solutions mean that a deviation route becomes obligatory and the impact on a given road network can be considerable, especially in urban areas.

Depending on local circumstances, the traffic diversion route may be very long. The risks and costs of a long detour over a short period must be balanced against the risks and costs of a partial tunnel closure over a longer period. It is possible to calculate the costs of detours, including the extra kilometres and delays, to back-up and/or support a decision. Any planned closures must be coordinated in advance with the operators of the roads used for rerouting traffic.

If it is technically possible, if the traffic is low and diversion roads are not practical, an alternate traffic system may enable the tunnel to remain open.

In the event of closure, good advance preparation is essential and can significantly reduce disruption. Regional and/or nationwide publicity in advance of the closure is important (e.g. television, radio, internet, billboards, publication of telephone numbers for information and complaints).

Once the tunnel is closed, diversion signs and signals should be used to provide information to users as far upstream as possible, before the relative points of choice, which are sometimes located at a considerable distance from the tunnel. For users who are relatively close to the tunnel, they must be informed of the closure and the alternative route before the last point of choice.

When it is inevitable that refurbishment/upgrading work must be carried out while traffic is present, specific traffic management measures must be adopted upstream from and inside the tunnel. In tunnels with two or more tubes, it is possible to close a tube completely and either establish bi-directional traffic in the other tube or establish a deviation route for users of the closed tube. If bi-directional traffic is established in the other tube, there is less inconvenience to users, as they do not have to take a deviation route. However, in terms of safety, this solution is far from ideal (and should be avoided in heavily trafficked tunnels) since it leads to users driving in opposing directions and hence an increased risk of accidents. This risk can be reduced by the use of VMS and overhead lane control signs. In the case of three-lane tubes, the centre lane should, if possible, be kept free of traffic as a buffer safety zone. Additional traffic management measures such as speed limit reductions and the implementation of an obligatory distance between vehicles should also be envisaged.

Where a tube is not completely closed to traffic and simple lane closures are implemented, they should always start before the entrance portal. Traffic should first be merged into the slower moving lane, then moved to the lane available at the incident site before entering the tunnel. In urban tunnel approaches this may not always be possible. Preferably lane closures should run for the full length of the tunnel. A situation where traffic is required to change lanes inside the tunnel is generally not recommended. However, in the case of longer tunnels, it may be advantageous to allow traffic to diverge and use all lanes once clear of all of the work sites. A risk assessment can result in the safest method for the situation.

Once again, additional traffic management measures such as speed limit reductions and the implementation of an obligatory distance between vehicles should also be envisaged.

Addition information on traffic management measures during tunnel closures can be found in PIARC report 2008R15EN: “Urban Road Tunnels: Recommendations to Managers and Operating Bodies for Design, Management, Operation and Maintenance”.

Following construction, the unavoidable deterioration of tunnel ventilation equipment reduces the ability of the system to maintain the required safety and performance levels. In addition, new safety measures may be required for technical reasons or because of changes in the tunnel environment.

Appendix A.5 "Ventilation systems" of the PIARC report 2012 R20 "Assessing and improving safety in existing road tunnels" identifies some examples of weak spots for existing tunnels, explaining why it is often necessary to make modifications to the ventilation systems of existing tunnels, including among others the following:

In addition, chapter 6 "Ventilation" of the PIARC report 2016 R19 "Complex Underground Road Networks", explains the reasons that make the refurbishment of the ventilation systems of the complex networks considerably more complicated than in conventional tunnels and section 3.1 "General aspects relevant for design and refurbishment" of the PIARC report 2008 R15 "Urban Road Tunnels: Recommendations to managers and operating bodies for design, management, operation and maintenance" explains some general aspects that also impact the capacity to conduct refurbishment programs for this kind of infrastructure.

Increasingly, road designers select tunnels as a good alternative, considering the ability of road tunnels to reduce some components of the environmental impact such as visual intrusion of infrastructures and noise pollution. Nevertheless some impacts remain or are even increased by such a choice. Despite all policy efforts to try to control and even reduce traffic, it is expected that traffic will increase during the next decades; so environmental issues linked to road traffic need to be considered.

The PIARC tunnel committee specifically investigated air pollution phenomena in depth, considering:

In fact, when considering air pollution, choices concerning the type of ventilation system determine the basis for designing the locations and flow rates of exhaust air; the operation regime and air quality settings for the ventilation control can often be more effective in delivering the required targets for local pollutant concentration than the selection of more complex ventilation systems.

Road traffic and (consequently) vehicle emissions constitute a serious environmental concern particularly in confined spaces such as tunnels. These emissions are characterized by the presence of various pollutants, which, at high concentrations, can cause adverse effects and consequences. The PIARC tunnel committee traditionally assesses vehicle-induced emissions and air quality inside tunnels. To this purpose, common modelling theories are reviewed, relevant air quality standards are defined and existing conditions are characterized. Measured and simulated pollutant concentrations are compared with air quality standards. Finally, mitigation measures are proposed to ensure proper air quality management inside the tunnel. Additional information on this aspect can be found in PIARC technical report 2019R02EN: “Road Tunnels: Vehicle Emissions and Air Demand for Ventilation” .

Tunnel air temperature may be a significant environmental issue in very long tunnels due to the heat that emanates from vehicles, and in tropical countries where the ambient temperature is already high outside the tunnel. In such cases, tunnel users such as motorcyclists and motorists in naturally ventilated vehicles may be subjected to unacceptable air temperature inside the tunnel. Solutions to excessive tunnel air temperatures have been sought through mechanical ventilation and also through the spraying of water into the tunnels, i.e. using the latent heat of evaporation to cool the tunnel air.

Tunnel emissions affect the air quality within a relative short distance from the points where emissions are dispersed, however the adjacent road network influences the environment in a broader area. Accordingly the air quality implications of tunnels should be examined in the context of the outside road network of which they are a part (see page on Tunnel impact on outside air quality).

Other important environmental issues are noise and vibration. Noise pollution can arise during the phase of construction causing environmental hazards, because a high noise level is often generated. In addition, high volumes of vehicles during normal traffic operation can generate large noise levels, which may be above permitted levels. Increasingly, noise pollution tends to be a problem adjacent to highly trafficked roadways.

The strategies for noise abatement follow long-established standard procedures in the planning and construction process. Major steps forward have been made to abate noise at the source: the use of special noise-absorbing pavements can reduce it, sound insulating and sound proofing barriers have become more and more efficient, as well as the use of combined features and the deployment of improved construction machines can minimize the generation of noise and vibration (see page on Noise and vibration).

Water impact is another aspect that has to be analysed during the life cycle of an infrastructure such as a tunnel. Detailed investigation of surface and subsurface hydrology should take place before and during construction. The least damaging route and structural elements should be chosen to get minimum interruption and alteration of hydrology patterns and processes. Drying up caused by the manner of building infrastructure is a topic which is becoming more and more important. Several studies can be carried out, which give insight into the effects of infrastructure on the hydrology of areas in the surroundings of tunnels and how to mitigate these effects. Water pollution caused by the leakage of construction materials during worksites can be reduced using containers that are designed to exclude leakage. Once the tunnel is in operation, water pollution caused by the cleaning of the tunnel must be also taken into account (see page on Water impact).

The final objective of tunnel designers and managers is to achieve sustainable operation from both a functional and an environmental point of view, in order deliver a reasonable level of safety and to reduce as far as possible any negative impacts on the environment. Different elements to improve the operational sustainability of tunnels are considered and analysed in technical report 2017R02EN: Road tunnel operations: First steps towards a sustainable approach (see page on Sustainable operation).

Energy consumption is a growing concern for tunnel owners and operators and should be taken into account in the construction phase (by adapting the design to less energy-intensive construction methods) and is essential in the operational phase. Ventilation and lighting systems can notably be optimized and in addition to the environmental benefits reaped, such optimization measures can sometimes lead to non-negligible cost reductions (see page on Sustainable energy consumption).

In the field of road tunnels, air quality is traditionally considered in relation to the level of concentrations of vehicle exhaust inside a tunnel. However, the concentrations of pollutants outside a tunnel can be harmful or annoying to people. Such pollutant concentrations rapidly reduce from a portal or exhaust shaft to the surrounding environment according to complex mechanisms such as the speed and direction of the wind and the neighbouring topography. Consequently, it is recognized that air quality in the vicinity of tunnel portals or other exhaust points is of interest when the traffic intensity increases and when tunnels are constructed in an urban environment.

Above a tunnel, the air quality is expected to be better than if an open air road section was situated at the same location. However at the portals and shafts, polluted air is set free when a longitudinal or transverse airflow is discharged by the piston effect of traffic and/or by ventilation systems.

Depending upon background concentrations and other sources localized close to a tunnel portal or shaft, the concentration levels of pollutants can exceed the maximum levels set by authorities. In that case measures must be taken to improve the air quality in the vicinity of the tunnel. Measures may include civil or mechanical works, planning of the land use around the tunnel, etc. Most often it may be possible reduce the pollution concentrations based on operational measures such as changes in the ventilation regime. Chapter III “Environment” of the 1996 PIARC report 05.02 “Road Tunnels: Emissions, Environment, Ventilation” provided background information on the behaviour of a tunnel air jet from portals.

PIARC has published the Technical Report 2008 R04 "Road Tunnels: A Guide to Optimizing the Air Quality Impact upon the Environment", which focuses on outside air quality related to tunnels and it is a guide to enhancing the urban environment by altering the emissions from vehicles and changing their spatial distribution within the space surrounding a tunnel. The guide considers a wide range of design and operation opportunities to mitigate the impact of tunnels on outside air: from the selection of the most optimum location of a tunnel, to gradients, ventilation type, air discharge management, traffic management, tunnel maintenance and finally (if still useful) contaminant removal techniques (see also Section 4.4.5 "Air cleaning" of the PIARC report 2017 R02 "Road Tunnel Operations: first steps towards a sustainable approach").

The environmental issues linked to ventilation, besides the energy consumption and the related carbon footprint, are linked to the localised, concentrated discharge of polluted air from the portals and stacks. Reducing their impact on the tunnel surroundings is part of good environmental design : see Section 4.3. "Tunnel air dispersion technique", Section 4.6. "Operational aspects" and Appendix D. "Overview of dispersion modeling in designing ventilation systems" of the PIARC report 2008 R04 "Road Tunnels: A Guide to Optimizing the Air Quality Impact upon the Environment".

Additional information specific for complex tunnels can be found in section 8.1 "External Air Quality" of the PIARC Report 2016 R19 “Road Tunnels: Complex Underground Road Networks”.

Noise is generally regarded as one of the key nuisances perceived by humans, which can significantly affect urban areas. It should therefore be taken into account in the design of tunnels, especially for those urban tunnels that have a high concentration of acoustical receptors in the immediate vicinity of portals and shafts.

Traffic-generated noise is not specific to tunnels. Underground infrastructures are generally regarded as having a positive influence on the acoustic environment, but there might be specific issues near the portals in some configurations. In most developed countries, noise impact studies are performed for every new infrastructure project (or significant modification), and the existence of tunnels is, of course, to be taken into consideration.

Figure1: Example of a noise barrier above a tunnel portal in an urban area

There are also sources of noise that are associated with the tunnel infrastructure, the main one of which is the ventilation system. In the case of transverse ventilation, or longitudinal ventilation with extraction shafts, fans and air flow through inlets and outlets may generate significant noise, and in some cases they have to function even at night time when noise environmental standards are set at lower targets. One solution may be to reduce the use of the ventilation system by optimising its control, but this can only be achieved to a limited extent.

The most effective solution is to take these problems into account at the design stage. Considering that the most prominent noise effects are geographically limited, air inlets/outlets may be located as far away as possible from neighbouring buildings, but this may result in significant increases in cost. The air velocity should be kept at relatively low values at air inlets/outlets to reduce noise generation by making the size of these openings large enough. Additionally, silencers are most often necessary to prevent the noise generated by the fans from "leaking" out of the ventilation plant.