The tunnel environment influences the hazards of road traffic in a specific way:

Hence in tunnels there is a trend towards less frequent, but (much) more severe incidents.

Tunnel safety studies typically focus on significant incidents, which have the potential to develop into events with serious consequences, mainly with collisions and fires. Furthermore, the manifold hazards potentially caused by dangerous goods require special attention. As an unrestricted availability of underground traffic infrastructure is crucial for economy as well as mobility, in particular on major transport axis and in areas with high traffic loads like big cities, events potentially causing significant traffic interruptions are additionally put into the center of attention. In this context security aspects have been gaining importance in the recent years.

Alternative propulsion technologies, including battery-electric vehicles, are becoming more prevalent. Whilst such vehicles remain a small overall proportion of the vehicle fleet, the combination of impacts of Government policy and technological advances in alternative fuels is expected to accelerate their increase in numbers on the road and in tunnels in coming years. The technical report Impact of New Propulsion Technologies on Road Tunnel Operations and Safety - Literature review reflects investigations carried out.

PIARC defines the term “incident” in the following way: An incident is an “abnormal and unplanned event (including accidents) adversely affecting tunnel operations and safety”.

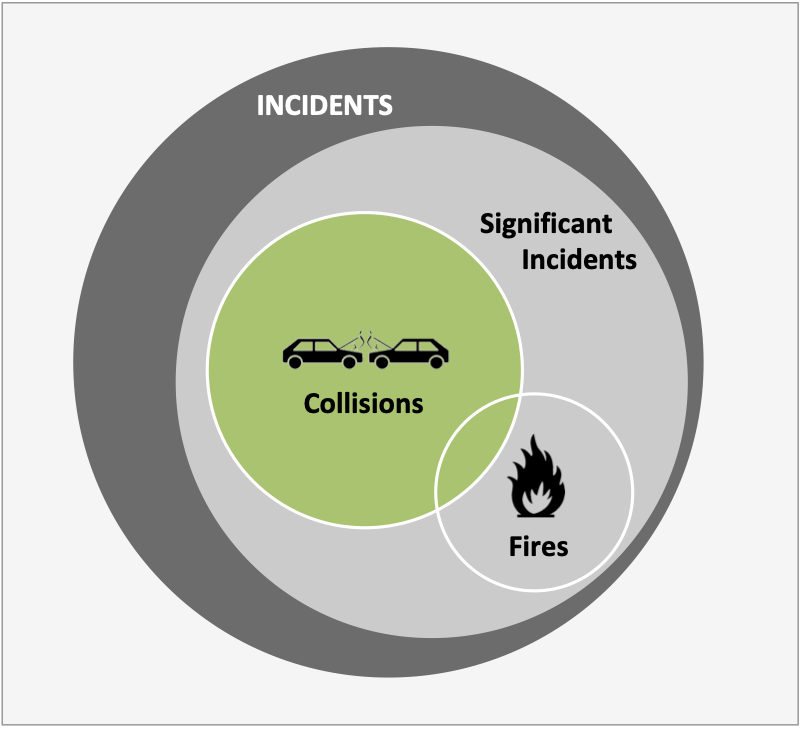

Figure 1: Illustration of the relationship between incidents, significant incidents, collisions and fires

The basic understanding of these terms is illustrated in Fig.1.

Traffic safety is a key success factor for road tunnel safety. In general, on a yearly basis, most injuries and fatalities in tunnels are related to traffic incidents that could also happen on the open road. However, since a tunnel is an enclosed space, the escalation of a collision, in terms of fire and the release of dangerous goods, could have far more serious consequences than on the open road, because more people than those directly involved in the incident can potentially be exposed to the hazards of heat, smoke, explosions or toxic gases. Moreover, the tunnel itself can contribute to the cause or the effects of a collision, for instance because of changing light conditions (the “black hole effect” when entering the tunnel) or because the tunnel wall is an “unforgiving obstacle” that can worsen the mechanical impact of a collision or impede a successful evasive manoeuvre.

To summarize:

Compared to the open road, there are several factors that may influence the probability or the effect of a collision in (and nearby) tunnels in a positive or negative way:

Positive:

Negative:

All in all, the tunnel manager must consider traffic safety in a specific tunnel in terms of risks and measures; he must analyse and evaluate the risks (on the basis of criteria for both traffic safety and tunnel safety) and he must consider, choose and implement measures to control these risks. For new to be built tunnels, this has already to be taken into account in the planning and design phase. For existing tunnels, the tunnel manager has to evaluate the safety situation in practice (feedback from experience, learning from actual incidents or near-incidents) and take measures to improve the situation when necessary.

Of course, not all the causes, like drunk driving, mobile phone use while driving, or the defective technical condition of a vehicle, are within the circle of influence of the tunnel manager. The same goes for the effects of the collisions. However, the tunnel related causes and effects can be effective targets for the measures to reduce the risk of collisions.

More qualitative and quantitative information that is useful for the risk assessment of collisions in road tunnels can be found in the report 2016/R35 “Experience with significant incidents in road tunnels”, notably in chapter 3. In the cycle 2016-2019, WG2 (Safety) of TC D.5 (Road Tunnel Operations) is drawing up a report “Prevention and mitigation of tunnel related collisions” on the (cost) effectiveness of the various measures that are at the disposal of the tunnel manager to control the collision risks.

Other useful reports on the subject include:

Among the possible risks to be considered in road tunnels, vehicle fires give rise to particular concern because they are not very rare events and their consequences may be far larger underground than in the open if no appropriate measures are taken.

The discussion on tunnel fires is often dominated by the extreme events which occurred in the Mont Blanc tunnel, the Tauern tunnel and the Gotthard Tunnel. However, in reality the majority of tunnel fires are relatively small events in comparison, which nevertheless may have the potential to develop into more serious events, depending on various influencing factors. The confined space of a tunnel provides an environment in which untenable conditions may develop rapidly in case of a fire. Series of real fire tests have been performed in the context of various national and international research programs in order to confirm assumptions on fire sizes and fire behaviour; in these tests the focus again was on large scale fires with high heat release rates.

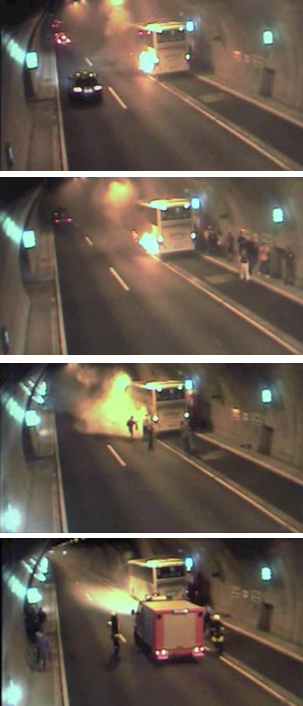

Fig. 1: Photo series showing a bus fire in a bidirectional tunnel: the bus on fire stops in a lay-by and the passengers evacuate to the emergency exit just on the opposite side of the location

There are a few key parameters for the characterisation of a tunnel fire: The speed of fire development and the fire size are of significant importance with regard to tunnel safety. Both are influenced by the nature of the fire load, the technical conditions of the vehicles involved, the airflow conditions in the tunnel during fire development as well as the fire safety engineering design of the specific tunnel. The maximum heat release rate of a fire depends on the quantity and type of material of the fire load as well as the boundary conditions of oxygen supply, tunnel characteristics and system response etc.. Fires in personal vehicles rarely develop to high heat release rates, whereas fully developed fires in the cargo of heavy goods vehicles and pool fires of burnable liquids potentially can develop into very high heat release rates.

Two types of tunnel fires (triggered by a collision or a vehicle defect) can be distinguished with regards to their characteristics: fires resulting from vehicle defect typically start in engine, exhaust system, wheels or brakes; seldom in the load. These fires in most cases are shielded fires which are likely to develop slowly in the first phase, with progressive development in later phase resulting in a fully developed fire. This type of fire development increases the opportunity to extinguish a fire (or delay its further development) either by the use of manual fire extinguishers, fixed fire fighting systems and/or by responding fire fighters, before it is able to threaten the health and safety of people in the tunnel. Fires after collisions are often accelerated by (limited amounts) of fuel that has leaked as a result of the collision, hence the development is typically faster. Flammable liquid fires, i.e. pool fires with large amounts of flammable liquids, are extremely rare occurrences, which require a large amount of flammable liquid to be released (as a consequence of a collision or by other reasons).

In Chapter 4 of the technical report 2016 R35 « Experience with significant incidents in road tunnels » new information on fires rates has been compiled, based on tunnel fire statistics from 12 countries around the world. The collection of data for statistical purposes requires a clear definition of events which should be considered as fires. Today there is different practise in different countries on what event is recorded as a fire and what is not; in the context of this report the defintion of the term « fire » according to the Norwegian Directorate for Civil Protection has been applied: a fire is“an unwanted or uncontrolled combustion process characterised by heat release and accompanied by smoke, flames or glowing”.

It seems that an “average tunnel” has a fire rate in the order of magnitude 5 – 15 fires per billion vehicle km. However, the scatter of the rates from tunnel to tunnel may be very significant as a number of factors may influence the recorded fire rates, for instance: tunnel design, location of the tunnel, geometry of the road, monitoring, technical standard of the vehicles, traffic regulation, speed limits, driving culture etc., hence the fire rates should be used with care and the assessment of the applicability and the modification of the basic rates required for an application for a given tunnel should be done by experts with experience in tunnel safety.

To get statistical information on type and severity of fire events is an even more complex issue. Therefore expert opinion is required in addition to the knowledge and information available from real fire incidents and real sclae fire tests. Based on recordings from Austria, Italy and South Korea, some indications are presented in Chapter 4.6 of the report 2016 R35« Experience with significant incidents in road tunnels ».

An understanding of how smoke behaves during a tunnel fire is essential for every aspect of tunnel design and operation. This understanding will influence the type and sizing of the ventilation system to be installed, its operation in an emergency and the response procedures that will be developed to allow operators and emergency services to safely manage the incident. Detailed discussion on the topic can be found in Section III "Smoke behaviour" and Section 1 "Basic principles of smoke and heat progress at the beginning of a fire", which analyse in detail the influence of different parameters (traffic, fire size, ventilation conditions, tunnel geometry) in the development of an incident.

Some randomly selected examples of real tunnel fires (including a short discription and analysis of the event) can be found in Appendix 5 of the technical report 2016 R35 “Experience with Significant Incidents in Road tunnels"

Dangerous goods or hazardous materials are solids, liquids or gases that can harm people, other living organisms, property or the environment, considering their chemical or physical properties. A substance or a material presenting a particular hazard should be used, handled or transported taking into account the characteristics of that hazard. A substance or a material is considered dangerous when it:

A dangerous good can present more than one kind of hazard and therefore several risks. The different types of hazard that may occur during road transport are coded as:

The following table describes hazards posed by dangerous goods depending on their Class according to ADR classification.

|

Class number |

Class description |

Hazard description |

|---|---|---|

|

Class 1 |

Explosive substances or articles |

• may cause undesired uncontrolled explosion, • may cause gas expansion and generate blast wave, • may cause property and physical damage, • launch of fragments at high speed and long distances. |

|

Class 2 |

Gases |

• they may be flammable, • they may be oxidising or at risk of oxidation, • in enclosed and closed rooms it can cause asphyxiation without being perceived, • they may be toxic, • if they are under pressure they may cause rupture (with possible explosion of the container), • if they are refrigerated (cryogenic) they can endanger human tissues, or if the temperature of the container increases rapidly the pressure may cause an explosion; these gases may also be flammable. |

|

Class 3 |

Flammable liquids |

• cause of fire. |

|

Class 4.1 |

Flammable solids, self-reactive substances, polymerizing substances and solid desensitized explosives |

• flammability, |

|

Class 4.2 |

Substances liable to spontaneous combustion |

hazards of substances and articles of this Class are due to the possibility of their automatic ignition on contact with the air and without cause (spark or flame); on contact with oxygen they may self-ignite. |

|

Class 4.3 |

Substances which, in contact with water, emit flammable gases |

• creation of flammable gases, |

|

Class 5.1 |

Oxidizing substances |

• ignition, |

|

Class 5.2 |

Organic peroxides |

• easy ignition, |

|

Class 6.1 |

Toxic substances |

• danger to human health, |

|

Class 6.2 |

Infectious substances |

substances are hazardous because they contain micro-organisms (bacteria, parasites, viruses) that can cause infections in humans and animals; they may also contain bacteria, parasitic organisms or viruses without antidote in case of infection. |

|

Class 7 |

Radioactive material |

Hazards arising from the transport of contaminated radioactive substances

Radiation can affect humans externally or internally:

|

|

Class 8 |

Corrosive substances |

• damage to the skin, eyes, mucous membranes and tissue necrosis, |

|

Class 9 |

Miscellaneous dangerous substances and articles |

• hazard to health if they enter the respiratory system (asbestos) |

In the context of road infrastructure, in particular road tunnels, security is understood as the preparedness, prevention and preservation of a road infrastructure against exceptional man-made hazards. This definition of security is complementary to that of safety, which is defined as the protection of road infrastructure against unintentional events such as accidents and is covered by relevant standards. Thus, the key distinction between security and safety is that:

Security-relevant hazards which may affect road tunnel infrastructure, operations and users are e.g. terrorism, cyber-crime, theft or hoaxes.

In order to analyse the security level of an infrastructure and to decide about the implementation of protective measures, a security assessment should be conducted. The security assessment consists of a hazard and scenario analysis, a determination of the vulnerability of the asset and its important components (object level) and finally the consideration of the tunnel’s criticality (network level), meaning its importance for the road network as well as any interdependencies with other transport infrastructure and other sectors. In order to prioritize tunnels to be strengthened by protective measures, the criticality of the asset is the key criterion. It is recommended to rank elements of infrastructure according to their criticality before deciding on budget allocation for protective measures.

Regarding protective measures which could be implemented in order to strengthen security, there is generally a large overlap with safety measures (the boundaries between safety and security are often not clear). This overlap can be used to strengthen both safety and security and could help to get the necessary funding for protective measures. The same is valid for already implemented measures in existing road tunnels: many existing structural and operational safety installations could be used to prevent or mitigate both safety and security related events (e.g. cameras (CCTV) or incident detection systems (IDS)). Generally it is recommended to include security principles from the conceptual and preliminary design phases for a new tunnel (“Security by design”). Retrofitting an existing infrastructure with security measures is often much more expensive. When considering protective measures for existing structures, low budget security solutions in particular or measures with synergies with safety should be implemented. Additionally so-called “soft measures” should be taken into account (e.g. organizational measures, staff training, etc.).

For more detailed information refer to the technical report 2015 R01 “Security of road infrastructure”. The report contains also useful references and links to existing international literature as well as procedures and tools for security assessment. Some useful examples for protective measures are also mentioned in this report. Other PIARC outputs related to security that could be relevant are for example: