The key principle for road tunnel safety is the integrated approach describing the cybernetic model how a tunnel system with an acceptable safety level can be established and maintained throughout the life cycle of a tunnel. This process includes safety assessment principles – to decide on an analytical basis, whether the safety level of a tunnel is acceptable – as well as the feedback from practical lessons learned, based on the experience from past incidents.

The outcome of serious incidents may be significantly affected by human behaviour which can be difficult to predict. Human factors are relevant in the interaction with tunnel operators as well as with tunnel users.

A topic with specific relevance for road tunnel safety is the transport of dangerous goods. Therefor basic principles and regulations for the transport of dangerous goods through road tunnels are also addressed in this chapter.

The approach for the development of a safe system is not the simple adoption of all possible safety measures but is the consequence of a balance between the forecast risk factors and the safety measures.

With the establishment and development of international regulations, recommendations and guidelines, there is a need for a framework within which all aspects of tunnel safety are taken into account. Such a framework may contain the following principal elements:

These safety elements are described in the Chapter 5 "Elements in an integrated approach" of report 2007R07, "Integrated Approach to Road Tunnel Safety".

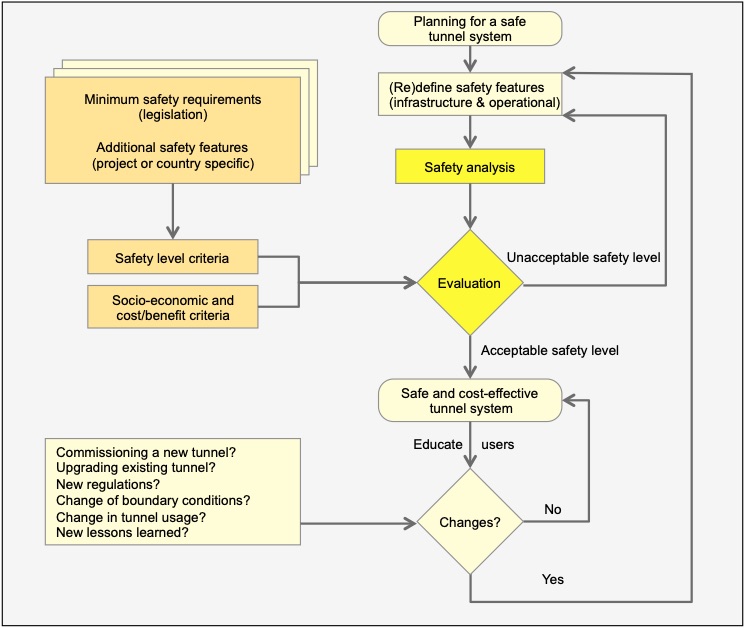

Figure 1: Integrated approach

An integrated approach is a framework to plan, design, construct and operate a new tunnel or an upgrade to an existing tunnel, fulfilling the required safety levels at each stage of the tunnel life. This should take place in accordance with a safety plan, following the appropriate safety procedures.

Fig. 1 shows a schematic representation of a proposed integrated approach for the safety of new and in-service tunnels, comprising the elements listed above. For more information, see Chapter 6 "Conclusion" of report 2007R07 and chapter 1 and chapter 7 of report 2016R35 which respectively address experience with the integrated approach.

In the past in many countries road tunnel safety to a great extent was based upon regulations and guidelines for the design, the construction and the operation of road tunnels: if the applicable prescriptions of relevant guidelines were fulfilled the tunnel was regarded as safe. These guidelines had been developed over decades and were mainly based on the experience of everyday operation, including incidents and accidents.

However, this prescriptive approach has some shortcomings which are particularly evident in incidents exceeding the range of existing operational experience:

Technical design specifications defined in guidelines are able to establish a certain level of standardization and to guarantee an adequate performance of the various technical systems; but this approach does not take into account the effectiveness of specific measures, which may be dependent on the specific conditions of an individual tunnel.

Further, even if a tunnel fulfils all regulative requirements it has a residual risk which is not obvious and not specifically addressed.

Hence, in addition to the traditional prescriptive approach, especially for complex systems a supplement is needed which specifically addresses emergency situations: the risk-based approach. Risk-based approaches allow a structured, harmonised and transparent assessment of risks for an individual tunnel, including the consideration of local conditions in terms of relevant influence factors, their interrelations and possible consequences of incidents. Moreover, risk-based approaches make it possible to propose relevant additional safety measures for the purpose of risk mitigation. Thus risk assessment can be the basis for decision-making considering cost-effectiveness in order to assure the optimum use of limited financial resources.

Therefore modern safety standards also take into account the evaluation of the effectiveness of safety measures based on risk assessment. In the European Union, for instance, the EC Directive 2004/54/EC on minimum safety requirements for road tunnels in article 13 introduces risk assessment as a practical tool for the evaluation of tunnel safety.

When performing risk assessment, it is important to realise that decision-making about risks is complex. Whereas risk analysis is a scientific process of assessment and/or quantification of probabilities and the expected consequences of identified risks, risk evaluation is a socio-political process in which judgments are made about the acceptability of those risks. Certain risk criteria have to be established to be able to evaluate the results of a risk analysis. In Chapter 4 of the technical report 2012 R23 “Current practice for risk evaluation for road tunnels” practically applicable risk evaluation strategies are presented.

The major fire incidents of Mont Blanc, Tauern and St. Gotthard (1999 and 2001) led to an increased awareness of the possible impact of incidents in tunnels. The likelihood of escalation of incidents into major events is low, however the consequences of such incidents can be severe in terms of victims, damage to the structure and impact on the transport economy.

An international survey of major tunnel fires can be found in the technical report 05.16B « Systems and equipment for fire and smoke control in road tunnels, Table 2.1 "Serious fires accidents in road tunnels".

These catastrophes demonstrated the need for improving preparation for, as well as preventing and mitigating, tunnel incidents. This can be achieved by the provision of safe design criteria for new tunnels, as well as effective management and possible upgrading of in-service tunnels, and through improved information and better communications with tunnel users. Conclusions drawn from the enquiry following the Mont Blanc tunnel fire were that fatal consequences could be greatly reduced by:

After the fire of March 24th 1999, the Mont Blanc tunnel required significant renovation before it was able to be reopened to traffic.

A detailed description of the Mont Blanc, Tauern and St. Gotthard fires including the original configuration of the tunnels, and a step-by-step guide to the incident, fire progression, and the behaviour of operators, emergency services and users, as well as the lessons to be drawn can be found in the technical report 05.16B « Systems and equipment for fire and smoke control in road tunnels. Chapter 3 "Lessons learned from recent fires". The lessons learnt are summarised in Table 3.5 of this report. Similar information is given in Routes/Roads 324 "A comparative analysis of the Mont-Blanc, Tauern and Gotthard tunnel fires" (Oct. 2004) on p 24.

However, characteristic events are fortunately rare, and may be limited to specific circumstances. Hence a systematic analysis of less severe, but more frequent incidents (collisions and fires) may provide a more representative picutre of real tunnel incidents. Appendix 5 of the technical report 2016 R35 “Experience with Significant Incidents in Road Tunnels” provides a survey of 32 randomly selected real tunnel incidents, including a short description as well as important conclusions and improvements that could be identified for specific types of incidents or tunnel systems.

Some lessons learned can be given as examples, such as:

However, it is not possible to give generally applicable recommendations on the basis of these findings because these may be different in dependence of the specific conditions of an individual country and an individual tunnel.

Moreover, this report presents updated statistical data on tunnel collisions (Chapter 3) and fires (Chapter 4) for many countries. The data base used for the calculations are enclosed in Appendix 3 (collisions) and Appendix 4 (fires) respectively.

Further, well-structured and reliable information on tunnel incidents is of great importance as input data for quantitative risk assessment as well as to motivate improvements in safety systems and procedures. These topics are also addressed systematically in the technical report 2016 R35 “Experience with Significant Incidents in Road Tunnels”.

Earlier reports also present a statistical census of breakdowns, collisions and fires in selected tunnels, as well as the lessons to be drawn from such events for the geometric design of the tunnel, the design of the safety equipment and the operating guidelines:

An adequate knowledge of human factors in the context of road tunnels optimises safety by acting in the direction of the user, the tunnel design and more generally, the organisation (tunnel operating body and emergency services). The focus of this chapter is on the interaction between the tunnel system and tunnel users; additional information is provided in the page "Human factors – Operators" regarding the interaction with tunnel staff and emergency teams.

The whole tunnel system, including the organisation of tunnel management, plays an important role in tunnel safety as it determines what the tunnel users see or have to respond to, in both normal and critical situations. The nature of the traffic regulations, motorists' compliance with them and the degree to which they are enforced contribute significantly to the level of tunnel safety. The properties of the vehicles using the tunnel and the loads they carry also play an important role.

Additional measures (with respect to the minimum requirements set by the EU-Directive) could be considered when focussing on human factors and human behaviour in terms of tunnel safety. Designing for optimal human use should include assessment of human abilities and limitations and ensuring that the resulting systems and processes that involve human interaction are designed to be consistent with the human abilities and limitations that have been identified. Human abilities and limitations refer to those physical, cognitive and psychological processes that deal with perception, information processing, motivation, decision-making and taking action.

The main conclusions regarding tunnel users are that:

Figure1: User approaching a tunnel

Designing for optimal human use should include assessment of human abilities and limitations and ensuring that the resulting systems and processes that involve human interaction are designed to be consistent with the human abilities and limitations that have been identified. Human abilities and limitations refer to those physical, cognitive and psychological processes that deal with perception, information processing, motivation, decision-making and taking action.

Technical Report 2008R17 "Human factors and road tunnel safety regarding users" deals with this topic. It discusses observations of the behaviour of tunnel users in both normal and critical situations and, in general terms, the main human factors that influence this behaviour. The report also formulates recommended measures, additional to the minimum measures required by the EU directive.

Technical report 2011R04 "Recommendations regarding road tunnel drivers' training and information" provides recommendations to all those in charge of education and information actions. The report develops proposals for educational elements for trainers, followed by practical instructions intended for the users. The document concludes with a number of suggestions and proposals that may be useful for the delivery of training and communication activities.

The main methodological recommendations to be implemented when it is desired to pay particular attention to human factors are:

The first point particularly concerns the design of new tunnels for which it is fundamental to intervene as far upstream as possible during the studies. This allows better account to be taken of the main factors which govern the behaviour of users in road tunnels. Among these main factors, the following can be notably mentioned:

The second point concerns making the best use of knowledge accumulated to date in the field of general road safety, and evacuation in crisis situations in particular. This can take shape in two ways: either by referring to general lessons learnt from work carried out in this field (PIARC recommendations for example), or by involving human science specialists (psychologists, experts) in the project. The lessons learnt from real events or from the numerous exercises held in tunnels show that the technical choices made by engineers specialised in the fields of equipment and safety in tunnels are not always the most appropriate from the viewpoint of user behaviour. Involving human science specialists should be considered for the most important projects (both new tunnels and refurbishments) with particular issues (cross-border and/or particularly long tunnels, tunnels of limited dimensions, complex tunnel structures, etc.)

Independent of the possible involvement of human science specialists, it is obviously necessary to take care to ensure a wide consultation of all the actors concerned at all times. In particular, the intervention services must be closely associated with the design of the safety equipment (particular attention must be given to features provided for self-help for evacuation of users).

The third recommendation concerns the tests and trials necessary to validate innovative choices when they are considered to be desirable. When it proves to be necessary to develop innovative means, the preliminary test phases must not be neglected (indoor testing for example), nor trials on site. These trials could be usefully performed with support from experts in the field of human sciences. Their objective will be to validate the innovative measures proposed before deployment in tunnels.

As a conclusion and in general, we emphasise the need to show much pragmatism and humility in this field. A basic principle consists in preferring simple and intuitive solutions whenever possible, in line with what is currently in practice in non-confined conditions. These types of approach ensure that the measures implemented are likely to be well understood and adopted by the users.

An adequate knowledge of human factors in the context of road tunnels optimises safety by acting in the direction of the user, the tunnel design and more generally, the organisation (tunnel operating body and emergency services). This chapter provides information regarding the interaction with tunnel staff and emergency teams.

Figure1: Road tunnel command post

The term "operator" describes the body representing the owner on site and is responsible for operating the tunnel. This key player for tunnel safety works in close relation with the other players concerned (owner, public authorities, emergency services, sub contractors, other operators, users, etc.). Its main task is to manage traffic, civil engineering aspects and tunnel equipment, together with crisis and administrative management related with its missions. It plays a crucial role for optimum implementation of the tunnel safety management system.

Lessons learnt from exercises and real events have shown that the behaviour of all those in charge of operating the tunnel is a decisive factor in ensuring the safety of people during an incident.

One of the key issues regarding this topic is the appropriate reaction of the operating staff responsible for monitoring and controlling tunnels. They are the very first to be involved in road tunnel crisis management and their task is all the more difficult in that they may at any time be required to manage potentially serious events for which the probability they will happen is extremely low. In the event of a serious incident that may require evacuation, they utilise various types of dynamic equipment that will enable them to inform and warn users in real time, whilst encouraging them to adopt the appropriate behaviour. This issue is dealt with in the technical Report 2016R06 entitled “Improving safety in road tunnels through real-time communication with users”. The report describes how to communicate information to users in normal, congested and critical conditions. It then details the various systems that could be activated in order to optimise real-time communication with users.

To react in the appropriate manner, tunnel operators must be able to understand and control sometimes complex situations, meaning they must be very good at stress management. Specific and appropriate training is thus essential. European regulations require the personnel involved in operating tunnels to receive "appropriate initial and continuing training" (European Directive 2004/54/CE - Annex 1 § 3.1 "Operating means").

Figure 2: Tunnel safety exercise with fire brigade

Rescue teams liable to be called on to intervene in road tunnels obviously need to have the general training required to help people and combat fires in any type of infrastructure. Tunnels are confined spaces in which a crisis or fire can very quickly render rescue operation conditions more complicated. Over and above their technical skills, firemen therefore need to be trained specifically for this type of intervention. This training must develop their behavioural knowhow and enable them to deal appropriately with the complex situations they may be confronted with in a tunnel. This knowhow is particularly crucial for the supervisory staff who must be capable under all circumstances of adapting the operational methods initially envisaged, if needed. In order to fulfill this mission, good coordination with the tunnel staff is critical, requiring meticulous preparation, follow-up and implementation of intervention plans, safety exercises, and training based on feedback of experience.

In the case of cross-border tunnels, attention needs to be drawn to the collaboration required between the countries concerned in order to ensure excellent coordination between the rescue teams in crisis situations.

Figure 3: Helping users in a shelter

With respect to the tunnel operator and the rescue teams, the technical Report 2008R03 "Management of the operator-emergency teams interface in road tunnels" discusses the most relevant lessons learnt from the most serious tunnel fires of the last decades. Based on experience and these lessons learnt, the report provides information and recommendations for best practice.

Regarding these players it can be concluded that it is of utmost importance for operator's staff and emergency services:

Dangerous goods are important for industrial production as well as everyday life, and they must be transported. However, it is acknowledged that these goods may cause considerable hazards if released in a collision, on open road sections as well as in tunnels. Incidents involving dangerous goods are rare, but may result in a large number of victims and severe material and environmental damage. Special measures are needed to ensure that the transport of dangerous goods is as safe as possible. For these reasons, the transport of dangerous goods is strictly regulated in most countries.

Dangerous goods transport raises specific problems in tunnels because an incident may have even more serious consequences in the confined environment of a tunnel as compared with incidents on the open road.

From 1996 to 2001, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and PIARC carried out an important joint research project to bring rational answers to open questions about transport of dangerous goods through tunnels: Transport of dangerous goods through road tunnels. Safety in Tunnels, Paris: OECD Publishing, 2001 ISBN 92-64-19651-X.

An international survey of regulations regarding the road transportation of dangerous goods in general and in tunnels showed that all investigated countries had consistent regulations for the transport of dangerous goods on roads in general, and that these regulations were standardised within large parts of the world. For instance, ADR (the European agreement concerning the international carriage of dangerous goods by road) is used in Europe and the Asian part of the Russian Federation. Most States in the USA and provinces in Canada follow codes in compliance with the UN Model Regulations. Australia and Japan had their own codes, but Australia has aligned with the UN system.

In contrast, the survey highlighted a variety of regulations regarding the transport of dangerous goods through tunnels. Restrictions applied in tunnels showed considerable variations between countries and even between tunnels within the same country. The inconsistency of the tunnel regulations posed problems for the organisation of dangerous goods transport and led a number of vehicles carrying dangerous goods to infringe restrictions..

As part of their joint project, OECD and PIARC made a proposal for a harmonised system of regulation. This proposal was further developed by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UN ECE), then implemented in Europe in 2007 and in further revisions of the ADR.

The harmonisation is based on the assumption that in tunnels there are three major hazards which may result in numerous victims or cause serious damage to the tunnel structure, and that they can be ranked as follows in order of decreasing consequences and increasing effectiveness of mitigating measures: (a) explosions; (b) releases of toxic gas or volatile toxic liquid; (c) fires. Restriction of dangerous goods in a tunnel is made by assigning it to one of five categories which are labelled using capital letters from A to E. The principle of these categories is as follows:

| Category A | No restrictions for the transport of dangerous goods |

|---|---|

| Category B | Restriction for dangerous goods which may lead to a very large explosion |

| Category C | Restriction for dangerous goods which may lead to a very large explosion, a large explosion or a large toxic release |

| Category D | Restriction for dangerous goods which may lead to a very large explosion, a large explosion, a large toxic release or a large fire |

| Category E | Restriction for all dangerous goods (except five goods with very limited danger) |

The decision on assigning a tunnel to one of these 5 categories can be based on risk assessment using risk assessment tools specifically developed for this kind of application.

More information on this topic is available on the following websites: